Analysing mWGS data

Session Overview

During this session we will cover the fundamentals of analysing metagenomic Whole Genome Shotgun (mWGS) sequence data.

1. An Introduction to mWGS Sequence Data

2. Estimating Bacterial Abundance from mWGS Data

2. Estimating Metabolic Pathway Abundance from mWGS Data

4. Searching for Genes with Interesting Function in mWGS Data

5. Visualizing mWGS Data Analysis Output with R

Session Three

1. An Introduction to mWGS Sequence Data

Similar to 16S analysis, the most common format in which to generate mWGS sequence data is fastq. For simplicity we will be working with single-end sequence data in this session, meaning there will only be one fastq file for each sample in our study. Navigate to the session directory and look at the sequence data that will be used in this session.

cd ~/MCA/mWGS/ # the parent directory

cd fastqs # the working directory containing our sequence data

ls

# Have a look at the first read in one of the fastq files

head -4 MET0109.subsample.fastq

@D0M0RACXX:7:2205:11381:62949/1

GCCAATCACCGTTACGAAATCGCCGTCTTTGAGATGGAGGCTGAGGTTTCGCAGGGCTCGTTTTTCGTTGACCGTGCCGGGGAAGAAGGTTTTTGAAATGG

+

CCCFFFFFHHHHHJJJJJJJJJIJIHHJJIIGIIHJJEHIIJJGJIHEHHGIHHFFFECD>BDDDD@DCCDDDD9<BDDDDD992<?CDCCCBBDBDC>C:Differences in the way that 16S and mWGS sequences are generated mean it is necesary to process the data differently. In particular, 16S analysis makes use of PCR primers that target and amplify the (bacterial) 16S gene. Only the 16S rRNA gene is sequenced, and it is safe to assume that all the sequence reads in our fastq files are bacterial in origin.

In contrast, mWGS sequencing uses random primers to target and amplify all regions of the metagenome. If there is non-bacterial DNA present in a sample (e.g. from the host), then it too will be targeted. Removal of host DNA contamination is an important step in processing mWGS data, particularly when limited amounts of DNA are available for sequencing. As this is a computationally demanding process, we will begin by assuming that host DNA has already been removed from our sequence data.

2. Estimating Bacterial Abundance from mWGS Data

As with 16S data, mWGS sequence data can be used to quantify the relative abundance of different bacterial taxa in microbiome samples. However, differences in the way these data are generated mean that they must be processed differently. Each approach has its strengths and weaknesses.

For example, two bacteria may be taxonomically (and functionally) different, but if this difference is not reflected in their 16S rRNA gene sequences, then 16S analysis will not be sufficient to tell them apart.

In contrast, mWGS sequencing can cover entire bacterial genomes and therefore has greater potential to distinguish closely related taxa. However, determining which mWGS sequences belong to which genomes is both complicated and computationally demanding, particularly when closely related taxa share large amounts of orthlogous sequence. Additionally, the random nature of mWGS sequencing means that coverage of different bacterial genomes may not be even. The genomes of some bacteria (e.g. those present at low relative abundance) may only be partly represented.

Most common approaches for quantifying bacteria with mWGS data involve mapping reads to databases of reference genes or genomes. Relative abundance of a single taxon can then be compared across samples by i) counting the number of reads mapped to its reference sequence within each sample and ii) normalizing counts to account for differences in sequencing effort (i.e. total number of reads generated) for each sample. Similarly, relative abundance of two different taxa can be compared within a sample by i) counting the number of reads mapped to each reference sequence and ii) normalizing to account for differences in reference sequence length. Typically data normalization is carried out to enable comparison of taxon abundance between and within samples. The result is that read counts are reported as fragments reads per kilo-base, per million reads, or RPKM.

2.b. Quantifying Bacterial Abundance with Metaphlan2

One tool that can convert mWGS data into taxon abundance estimates is Metaphlan2. Metaphlan2 avoids the issue of dealing with reads that map to homologous sequence by curating a set of unique clade-specific marker genes that distinguish different bacterial taxa. mWGS reads are first mapped to this reference geneset, then normalized.

Try running Metaphlan2 for a single sample.

# Make sure you are in the working directory for this session.

cd ~/MCA/mWGS/

pwd

# Before running Metaphlan2, lets see what time it is?

date

# Run Metaphlan2, providing a single sample as input

metaphlan2.py fastqs/MET0109.subsample.fastq --input_type fastq > MET0109_metagenome_profile.tsv

# How long did Metaphlan2 take to run?

date

# Have a look at the principal output of Metaphlan2

less MET0109_metagenome_profile.tsv

# Once you are familiar with the content of this file, you can delete it

rm MET0109_metagenome_profile.tsvWhat do the two columns in Metaphlan2 output represent?

What do the data in the second Metaphlan2 output file (MET0109.subsample.fastq.bowtie2out.txt) represent?

For additional information on Metaphlan2, including an explanation of these output files, see this online tutorial

2.c. Running Metaphlan2 with Pre-Mapped Fastq Files

Metaphlan2 performs two steps. The first maps reads to the reference gene set using the mapping tool bowtie2. The second counts the number of reads mapping to each clade-specific marker, performs normalization, and outputs a percent estimation for each taxon abundance.

It would be possible to run both steps sequentially for every fastq file in fastqs.

### Example code only, do not run during this session ###

# make a directory in which to store the two Metaphlan2 output files

mkdir metaphlan2_profiles

mkdir metaphlan2_mapped

# Run Metaphlan2 sequentially on all fastq files in ./fastqs

for FASTQ in fastqs/*fastq

do

# capture the file prefix, which corresponds to the sample name

SAMPLEID="$(basename ${FASTQ%.subsample.fastq})"

# run Metaphlan2

metaphlan2.py $FASTQ \

--input_type fastq \

--output_file metaphlan2_profiles/${SAMPLEID}_metagenome_profile.tsv \

--bowtie2out metaphlan2_mapped/${SAMPLEID}_bowtie2out.txt \

--nproc 4

# Print a helpful message after each completed Metaphlan2 run

echo Completed Metaphlan2 for $SAMPLEID on `date`

doneHowever, running the above code is time consuming, even when using --nproc 4 to run on multiple

cores. You will therefore find the pre-computed output of the first step already in the directory

./metaphlan2_mapped. It is then possible to run the second step independently.

### Warning: you may not want to run this code during the session ###

# make a directory in which to store the Metaphlan2 output file

mkdir metaphlan2_profiles

# Run Metaphlan2 sequentially on the output of the bowtie2 mapping step

for MAPFILE in metaphlan2_mapped/*bowtie2out.txt

do

# capture the file prefix, which corresponds to the sample name

SAMPLEID="$(basename ${MAPFILE%_bowtie2out.txt})"

# run Metaphlan2

metaphlan2.py $MAPFILE \

--input_type bowtie2out \

--output_file metaphlan2_profiles/${SAMPLEID}_metagenome_profile.tsv \

--nproc 4

done ### Alternative to running the above code ### # Copy the output directory from backup cp -r ~/MCA/backup/mWGS/metaphlan2_profiles .

Finally, Metaphlan2 also provides a python script that can be used to merge data for different samples into a single count matrix.

# python script for combining Metaphlan2 output

which merge_metaphlan_tables.py

# run this python script to generae a single count matrix

merge_metaphlan_tables.py \

metaphlan2_profiles/*_metagenome_profile.tsv \

> metaphlan2_counts.tsv Have a look at the merged count file. What do the first two lines in the file mean?

Which taxonomic level(s) are reported in this file?

By default Metaphlan2 outputs relative abundance estimates for all taxonomic levels to the same

file. While this is useful for some downstream analyses, others may require information for only

one taxonomic level at a time. Running the above code, but with the --tax_level g argument will

cause Metaphlan2 to only report genera abundance estimates. The resulting count matrix will then

be analogous to the OTU count matrix generated during 16S sequence analysis.

Rather than re-run Metaphlan2, we will use the command line tool awk to extract genera counts from our existing count matrix.

# some command line magic to extract genus counts

cat metaphlan2_counts.tsv | awk 'NR == 1 || $1 ~ /g__[A-Za-z]*$/' > metaphlan2_genera_counts.tsvAside from the taxonomic level reported, what other important differences exist between an OTU table and a Metaphlan2 genus abundance table?

2.d. Visualizing Metaphlan2 Taxonomic Abundance

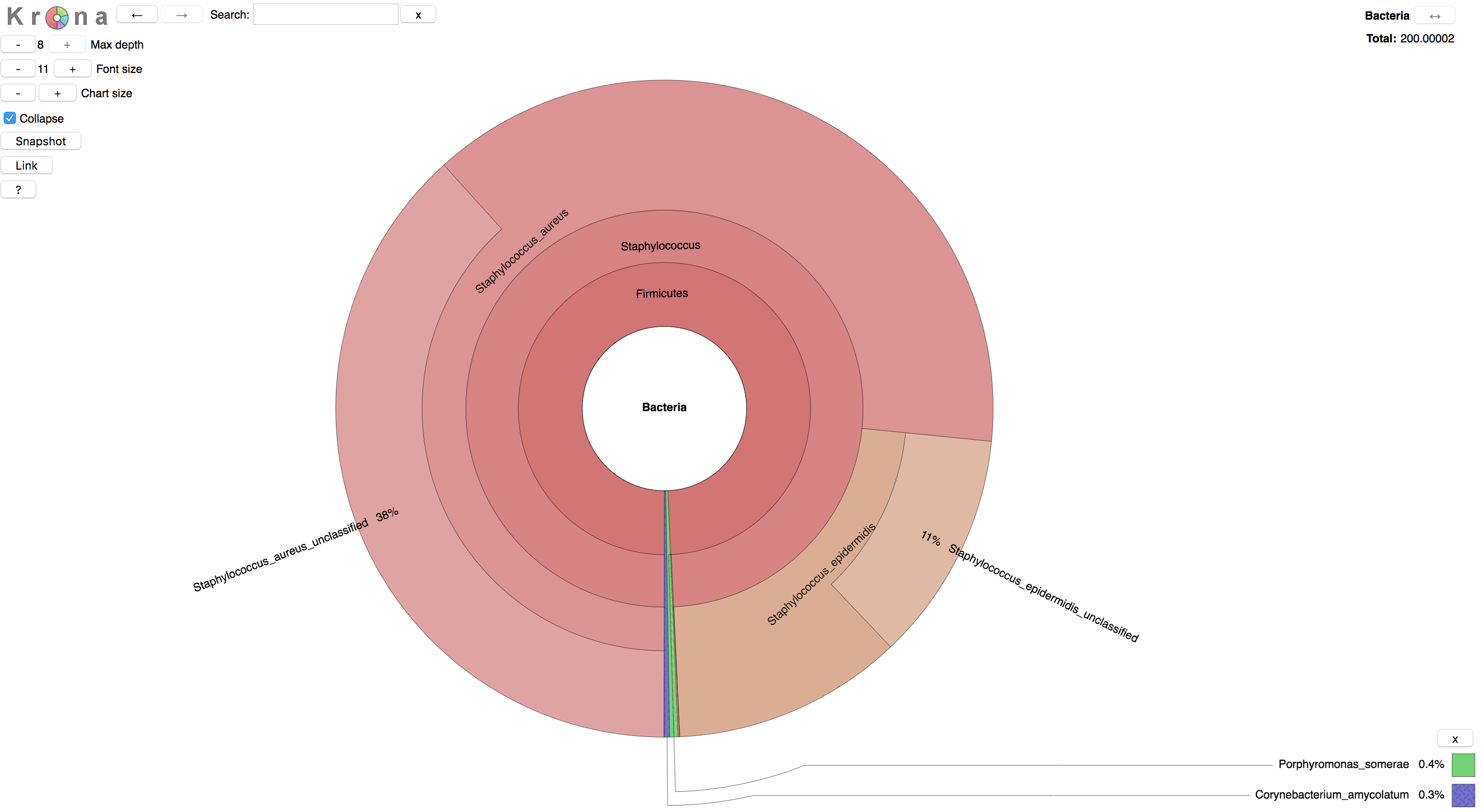

Metaphlan2 output can be visualized in a variety of ways. One is via the metagenome visualization tool Krona. Metaphlan2 provides a convenience script for converting output into the format required by Krona.

mkdir metaphlan2_krona

# Convert Metaphlan2 output into the format required by Krona

for PROFILE in metaphlan2_profiles/*_metagenome_profile.tsv

do

# capture the file prefix, which corresponds to the sample name

SAMPLEID="$(basename ${PROFILE%_metagenome_profile.tsv})"

# run script to convert profile to format required by Krona

metaphlan2krona.py --profile $PROFILE --krona metaphlan2_krona/${SAMPLEID}_krona_file.tsv

# run Krona to generate interactive html file

ktImportText metaphlan2_krona/${SAMPLEID}_krona_file.tsv \

-o metaphlan2_krona/${SAMPLEID}_krona_file.html

doneTry downloading some of the html files created by Krona.

Have a look at the taxonomic composition of your samples.

The result should look something like this:

3. Estimating Metabolic Pathway Abundance from mWGS Data

While both 16S and mWGS data can be used to estimate the relative abundance of different microbial taxa, mWGS data can also provide insight into the metabolic potential of the microbiome. This can be done by mapping mWGS reads to databases containing genes with known metabolic function.

The developers of Metaphlan2 provide a second tool HUMAnN2. Similar to Metaphlan2, HUMAnN2 maps mWGS reads to a reference database; however this database was generated by i) taking all bacterial genes present in the NCBI reference database, ii) clustering genes based on their sequence similarity, and iii) inferring the metabolic function of each gene cluster by comparing it to genes in the UniRef reference database.

The HUMAnN2 reference database is large - too large to be installed on the cloud instance used for

this practical session. Instead the output for a HUMAnN2 run is provided in the sub-directory

./humann2_output. It would be possible to generate these output files for every file in fastqs.

### Example code only, do not run during this session ###

mkdir humann2_output

# First convert fastq files to fasta format for use with HUMAnN2

for FASTQ in fastqs/*fastq

do

# capture the file prefix, which corresponds to the sample name

SAMPLEID="${FASTQ%.fastq}"

# run fastq_to_fasta

fastq_to_fasta -i $FASTQ -o $SAMPLEID.fasta

done

# run HUMAnN2

for FASTA in *fasta

do

# The capture the file prefix

SAMPLEID="$(basename ${FASTA%.fasta})"

humann2 \

--input $FASTA \

--output humann2_output \

--nucleotide-database /path/to/humann2/nucleotide/database \

--protein-database /path/to/humann2/protein/database \

&> $SAMPLEID.log

echo Completed HUMAnN2 run for sample $SAMPLEID

doneIn order to improve the chance of finding a match, HUMAnN2 maps each read first to a database of nucleotide sequences, then to a database of protein sequences. It outputs a variety of files into a specified subdirectory.

Navigate to the output directory for a single HUMAnN2 run. Have a look at the different files in this directory.

In particular have a look at the three files with the suffixes_genefamilies.tsv,_pathabundance/tsv, and_pathcoverage.tsv

cd humann2_output

# A table of gene abundance

head MET0109_genefamilies.tsv

# A table of pathway abundance

head MET0109_pathabundance.tsv

# A table of pathway coverage

head MET0109_pathcoverage.tsvHUMAnN2 outputs a count of the number of reads mapping to each gene in its reference database to the

file ending _genefamilies.tsv. However, genes alone are not particularly informative, therefore

HUMAnN2 also combines information from all the genes that contribute to a single metabolic pathway

and provides an outputs an estimate of pathway abundance to the file ending _pathabundance.tsv.

Finally, HUMAnN2 also outputs a confidence estimation of whether a particular metabolic pathway is

detected in a sample to the file ending _pathcoverage.tsv. For a detailed explanation of these

files, including how HUMAnN2 calculates pathway abundances from constituent gene abundances, see

here. For a detailed descriptoin of the metabolic pathways used by HUMAnN2, see

here.

Having created estimates of gene and pathway abundance for each sample, it is necessary to i) normalize data to account for differences in sequencing effort and gene/pathway size, and ii) merge normalized data into a single count matrix.

# Navigate back to the working directory

cd ~/MCA/mWGS/

# Normalize pathway abundance counts for each sample

for FILE in humann2_output/*pathabundance.tsv

do

SAMPLEID="${FILE%.tsv}"

# Run HUMAnN2 to normalize counts to 'counts per million reads mapped'

humann2_renorm_table --input $FILE --output ${SAMPLEID}_cpm.tsv --units cpm

done

# combine the pathway abundance estimates

humann2_join_tables \

--input humann2_output \

--output humann2_pathabundance_cpm.tsv \

--file_name _pathabundance_cpmHave a look at the resulting merged file.

Try normalizing and merging the files containing HUMAnN2 gene abundance and/or path coverage estimates.

As mentioned, HUMAnN2 clusters NCBI genes based on sequence similarity before it annotates them

with a particular metabolic function. It is therefore able to provide an abundance estimate for

each every gene within a cluster, as well as for the cluster itself. Within the output file,

you will see that some rows are labelled first by the UniRef ID for the clyster, followed by a

pipe |, followed by the taxonomy (genus.species) of the contriuting gene. Other rows are just

labelled by the UniRef ID for the cluster. The latter contain abundance estimates for that

gene/pathway cluster.

To simplify downstream analysis, we will use the command line tool grep to extract the abundane

estimates for each gene cluster and discard the abundance estimates for individual genes.

An alternative to this would be to use the --remove-stratified-output command as described in the

HUMAnN2 documentation.

# Some command line magic to remove individual gene counts from HUMAnN2 output

cat humann2_pathabundance_cpm.tsv | grep -v "|g__" | grep -v "|unclassified" > humann2_filtered_pathabundance.tsv

4. Searching for Genes With Interesting Function in mWGS Data

It is also possible to search mWGS data for evidence of genes whose function is of a priori interest. In this session we will search for evidence of genes assiociated with antibiotic resistance using the tool ShortBRED.

ShortBRED uses reference databases to identify unique ‘marker sequences’ that distinguish functionally related groups of genes (for example genes encoding beta-lactam resistance). It then identifies and quantifies these marker sequences within mWGS samples.

Start by looking at the pre-built reference database containing unique marker sequences that distinguish families of antibiotic resistance genes.

cd ~/MCA

cd data/mWGS

# The suffix .faa denotes a fasta file containing amino acid sequences

head ShortBRED_ABR_101bp_markers.faaNote that this fasta file contans protein sequences. As our data are nucleotide sequences it is necessary for ShortBRED to perform a translated alignment to search for marker sequences in our mWGS data. It does thus using USEARCH, which we encountered during 16S analysis.

Run ShortBRED for each mWGS sample to search for marker sequences that provide evidence of antibiotic resistance genes.

# Make sure you are in the session working directory

cd ~/MCA/mWGS/

# Create a sub-directory for ShortBRED output

mkdir shortbred_output

# Run ShortBRED

for FASTQ in fastqs/*fastq

do

SAMPLEID="$(basename ${FASTQ%.subsample.fastq})"

mkdir shortbred_output/${SAMPLEID}_dir

shortbred_quantify.py \

--markers ../data/mWGS/ShortBRED_ABR_101bp_markers.faa \

--wgs $FASTQ \

--results shortbred_output/${SAMPLEID}_shortbred.tsv \

--tmp shortbred_output/${SAMPLEID}_dir

done

# Have a look at the files generated by running ShortBRED

cd shortbred_output

ls

head MET0109_shortbred.tsvIn addition to the ShortBRED results files for each sample, what other files are present in the output directory?

For a detailed description of the output files generated by running ShortBRED, see here. Note that ShortBRED output is by default normalized to RPKM, so there is no need to perform additional normalization on these data.

The default ShortBRED output (specified by --results argument) contains four columns. However we

are only interested in the relative abundance. We will therefore extract this column before merging

the results for each sample into a count matrix.

# First it's necessary to extract the FPKM column from the ShortBRED output

# This can be done with the 'cut' command

for FILE in shortbred_output/*_shortbred.tsv

do

SAMPLEID="${FILE%_shortbred.tsv}"

cat $FILE | cut -f1,2 > ${SAMPLEID}_shortbred_subset.tsv

done

#It's then possible to use HUMAnN2 to merge the shortbred data

humann2_join_tables --input shortbred_output \

--output shortbred_abundance.tsv \

--file_name _shortbred_subset.tsvThe result of this analysis is a table listing the relative abundance of antibiotic resistance genes in our mWGS data. For other pre-built ShortBRED databases of unique ‘marker sequences’ see here

5. Visualizing mWGS Data Analysis Output with R

Steps Two, Three, and Four, outlined above have each generated a count matrix:

metaphlan2_genera_counts.tsvhumann2_filtered_pathabundance.tsvshortbred_abundance.tsv

As with 16S data it is possible to use R and RStudio to perform statistical analysis and provide visual summaries of these data. Open RStudio and set the working directory to be the directory containing the output of our mWGS analyses.

setwd('~/MCA/mWGS/')Start by loading some additional metadata associated with each sample

df.meta <- read.table('../data/mWGS/Metadata.csv', row.names=1, header=T, sep=',')

head(df.meta)There is no single R library that provides a convenient interface for analysing mWGS data. It is therefore necessary to perform data exploration manually. The following sections are intended to provide a brief overview of the potential for mWGS data exploration in R.

5.b. Exploring ShortBRED Results

First load the results file from the ShortBRED analysis shortbred_abundance.tsv.

# Load the ShortBRED results, in which rows are antibiotic resitance markers and columns are samples

df.shortbred <- read.table('shortbred_abundance.tsv', row.names=1, header=T)

head(df.shortbred)

# Remove the suffix from the sample labels

names(df.shortbred) <- gsub('_shortbred_subset', '', names(df.shortbred))

head(df.shortbred)

# Re-order the columns to that they correspond to the order of samples in df.meta

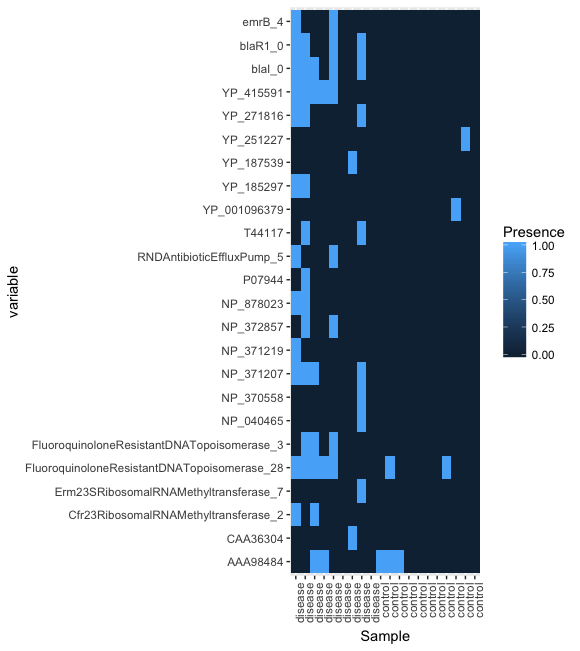

df.shortbred <- df.shortbred[,row.names(df.meta)]Next, generate a simple table that indicates the presence/absence of antibiotic resistance genes in each sample.

## Start by identifying and removing any row in which there are no counts

# which rows sum to zero?

rowSums(df.shortbred)

# remove rows that sum to zero

df.shortbred <- df.shortbred[rowSums(df.shortbred) !=0,]

# Convert our data to presence/absence

df.shortbred.b <- df.shortbred

df.shortbred.b[df.shortbred.b!=0] <- 1

# Transpose the binary table

df.shortbred.b <- data.frame(t(df.shortbred.b))

head(df.shortbred.b)It is possible to generate a heatmap that conventiently summarizes this information using the R library ggplot2. However, this requires some preliminary formatting of the R data frame.

# Add some extra columns to our table

df.shortbred.b$Condition <- df.meta$Condition

df.shortbred.b$Sample <- row.names(df.shortbred.b)

head(df.shortbred.b)

# Melt the dataframe

library('reshape2')

df.shortbred.b <- melt(df.shortbred.b,

id.vars=c('Condition', 'Sample'),

value.name='Presence')

# Plot the presence/absence heatmap

library('ggplot2')

pl <- ggplot(df.shortbred.b, aes(x=Sample, y=variable, fill=Presence)) + geom_tile()

pl <- pl + scale_x_discrete(labels=df.shortbred.b$Condition)

pl <- pl + theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 90, hjust = 1))

plot(pl)The result should look something like this:

Try plotting an equivalent heat map without converting values to presence absence.

5.c. Exploring HUMAnN2 Results

Using HUMAnN2 we generated normalized abundance estimates for metabolic pathways that have been annotated as part of the MetaCyc project. Start by loading the pathway abundance table into R. Note that due to the fact that pathway names are complex, extra care needs to be taken when parsing these data.

# Load HUMAnN2 results into R

# Be careful to specify the column separation and comment.char variables

df.humann2 <- read.table('humann2_filtered_pathabundance.tsv',

row.names=1, header=T, sep='\t',

comment.char='', quote='')

head(df.humann2)

# Remove the suffix from the sample labels

names(df.humann2) <- gsub('_Abundance', '', names(df.humann2))

head(df.humann2)

# Re-order the columns to that they correspond to the order of samples in df.meta

df.humann2 <- df.humann2[,row.names(df.meta)]

head(df.humann2)

# Have a closer look at some of the pathways in this data frame

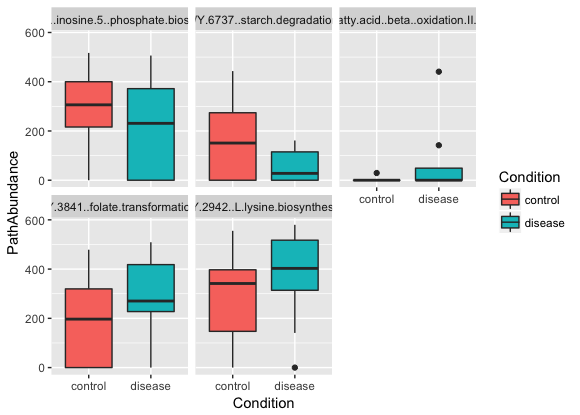

row.names(df.humann2)As there are ~2000 pathways in our data, we will select a smaller number to plot

# For simplicity, select five pathways at random

pathways <- c("PWY-7234: inosine-5'-phosphate biosynthesis III",

"PWY-6737: starch degradation V",

"PWY-5136: fatty acid β-oxidation II (peroxisome)",

"PWY-3841: folate transformations II",

"PWY-2942: L-lysine biosynthesis III")

df.humann2.sub <- df.humann2[pathways,]The R plotting library ggplot2 can again be used to provide visual summaries of these data. It is necessary to format the data for use with ggplot2.

library('ggplot2')

library('reshape2')

# Transpose matrix

df.humann2.sub <- data.frame(t(df.humann2.sub))

head(df.humann2.sub)

# Add some extra columns

df.humann2.sub$Condition <- df.meta$Condition

df.humann2.sub$Sample <- row.names(df.humann2.sub)

head(df.humann2.sub)

# Melt the dataframe

df.humann2.sub <- melt(df.humann2.sub,

id.vars=c('Condition', 'Sample'),

value.name='PathAbundance')

head(df.humann2.sub)

# Plot the five pathways of interest

pl <- ggplot(df.humann2.sub, aes(x=Condition, y=PathAbundance, fill=Condition))

pl <- pl + geom_boxplot()

pl <- pl + facet_wrap(~ variable)

plot(pl)The resulting plot should look something like this:

Try selecting and plotting other pathways in the HUMAnN2 output.

Conclusions

This session provides an introduction to the analysis of metagenomic shotgun sequence data. Targeting the entire metagenome offers greater scope for the interpretation of microbiome studies. However, the data are more complex, and excercisng biological judgement during all stages of data processing and analysis is therefore essential.

Here we have made use of three tools ( Metaphlan2, HUMAnN2, ShortBRED), which were all developed by the Huttenhower Lab. While support for mWGS analysis is not as extensive as 16S, there are other excellent tools available online. See, for example, MEGAN and tools arising from the MetaHIT project.