Introduction

Overview

Teaching: 0 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

Key question (FIXME)

Objectives

First learning objective. (FIXME)

FIXME

Key Points

First key point. Brief Answer to questions. (FIXME)

Why use cloud computing?

Overview

Teaching: 15 min

Exercises: 5 minQuestions

What is cloud computing?

Why would I be interested in cloud computing?

What can I expect to learn from this course?

Objectives

Be able to describe what an cloud computing system is

Identify how cloud computing could benefit you.

Frequently, research problems that use computing can outgrow the capabilities of the desktop or laptop computer where they started:

- A statistics student wants to cross-validate a model. This involves running the model 1000 times — but each run takes an hour. Running the model on a laptop will take over a month! In this research problem, final results are calculated after all 1000 models have run, but typically only one model is run at a time (in serial) on the laptop. Since each of the 1000 runs is independent of all others, and given enough computers, it’s theoretically possible to run them all at once (in parallel).

- A genomics researcher has been using small datasets of sequence data, but soon will be receiving a new type of sequencing data that is 10 times as large. It’s already challenging to open the datasets on a computer — analyzing these larger datasets will probably crash it. In this research problem, the calculations required might be impossible to parallelize, but a computer with more memory would be required to analyze the much larger future data set.

- An engineer is using a fluid dynamics package that has an option to run in parallel. So far, this option was not used on a desktop. In going from 2D to 3D simulations, the simulation time has more than tripled. It might be useful to take advantage of that option or feature. In this research problem, the calculations in each region of the simulation are largely independent of calculations in other regions of the simulation. It’s possible to run each region’s calculations simultaneously (in parallel), communicate selected results to adjacent regions as needed, and repeat the calculations to converge on a final set of results. In moving from a 2D to a 3D model, both the amount of data and the amount of calculations increases greatly, and it’s theoretically possible to distribute the calculations across multiple computers communicating over a shared network.

In all these cases, access to more (and larger) computers is needed. Those computers should be usable at the same time, solving many researchers’ problems in parallel.

Break the Ice

Talk to your neighbour, office mate or rubber duck about your research.

- How does computing help you do your research?

- How could more computing help you do more or better research?

A Standard Laptop for Standard Tasks

Today, people coding or analysing data typically work with laptops.

Let’s dissect what resources programs running on a laptop require:

- the keyboard and/or touchpad is used to tell the computer what to do (Input)

- the internal computing resources Central Processing Unit and Memory perform calculation

- the display depicts progress and results (Output)

Schematically, this can be reduced to the following:

When Tasks Take Too Long

When the task to solve becomes heavy on computations, the operations are typically out-sourced from the local laptop or desktop to elsewhere. Take for example the task to find the directions for your next vacation. The capabilities of your laptop are typically not enough to calculate that route spontaneously: finding the shortest path through a network runs on the order of (v log v) time, where v (vertices) represents the number of intersections in your map. Instead of doing this yourself, you use a website, which in turn runs on a server, that is almost definitely not in the same room as you are.

Note here, that a server is mostly a noisy computer mounted into a rack cabinet which in turn resides in a data center. The internet made it possible that these data centers do not require to be nearby your laptop. What people call the cloud is mostly a web-service where you can rent such servers by providing your credit card details and requesting remote resources that satisfy your requirements. This is often handled through an online, browser-based interface listing the various machines available and their capacities in terms of processing power, memory, and storage.

The server itself has no direct display or input methods attached to it. But most importantly, it has much more storage, memory and compute capacity than your laptop will ever have. In any case, you need a local device (laptop, workstation, mobile phone or tablet) to interact with this remote machine, which people typically call ‘a server’.

When One Server Is Not Enough

If the computational task or analysis to complete is daunting for a single server, larger agglomerations of servers are used. These go by the name of “clusters” or “super computers”.

The methodology of providing the input data, configuring the program options, and retrieving the results is quite different to using a plain laptop. Moreover, using a graphical interface is often discarded in favor of using the command line. This imposes a double paradigm shift for prospective users asked to

- work with the command line interface (CLI), rather than a graphical user interface (GUI)

- work with a distributed set of computers (called nodes) rather than the machine attached to their keyboard & mouse

I’ve Never Used a Server, Have I?

Take a minute and think about which of your daily interactions with a computer may require a remote server or even cluster to provide you with results.

Some Ideas

- Checking email: your computer (possibly in your pocket) contacts a remote machine, authenticates, and downloads a list of new messages; it also uploads changes to message status, such as whether you read, marked as junk, or deleted the message. Since yours is not the only account, the mail server is probably one of many in a data center.

- Searching for a phrase online involves comparing your search term against a massive database of all known sites, looking for matches. This “query” operation can be straightforward, but building that database is a monumental task! Servers are involved at every step.

- Searching for directions on a mapping website involves connecting your (A) starting and (B) end points by traversing a graph in search of the “shortest” path by distance, time, expense, or another metric. Converting a map into the right form is relatively simple, but calculating all the possible routes between A and B is expensive.

Checking email could be serial: your machine connects to one server and exchanges data. Searching by querying the database for your search term (or endpoints) could also be serial, in that one machine receives your query and returns the result. However, assembling and storing the full database is far beyond the capability of any one machine. Therefore, these functions are served in parallel by a large, “hyperscale” collection of servers working together.

Key Points

Cloud computing typically involves connecting to very large computing systems elsewhere in the world.

These other systems can be used to do work that would either be impossible or much slower on smaller systems.

The standard method of interacting with such systems is via a command line interface called Bash.

Working on a remote HPC system

Overview

Teaching: 25 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

What is an HPC system?

How does an HPC system work?

How do I log in to a remote HPC system?

Objectives

Connect to a remote HPC system.

Understand the general HPC system architecture.

What Is an HPC System?

The words “cloud”, “cluster”, and the phrase “high-performance computing” or “HPC” are used a lot in different contexts and with various related meanings. So what do they mean? And more importantly, how do we use them in our work?

The cloud is a generic term commonly used to refer to computing resources that are a) provisioned to users on demand or as needed and b) represent real or virtual resources that may be located anywhere on Earth. For example, a large company with computing resources in Brazil, Zimbabwe and Japan may manage those resources as its own internal cloud and that same company may also use commercial cloud resources provided by Amazon or Google. Cloud resources may refer to machines performing relatively simple tasks such as serving websites, providing shared storage, providing web services (such as e-mail or social media platforms), as well as more traditional compute intensive tasks such as running a simulation.

The term HPC system, on the other hand, describes a stand-alone resource for computationally intensive workloads. They are typically comprised of a multitude of integrated processing and storage elements, designed to handle high volumes of data and/or large numbers of floating-point operations (FLOPS) with the highest possible performance. For example, all of the machines on the Top-500 list are HPC systems. To support these constraints, an HPC resource must exist in a specific, fixed location: networking cables can only stretch so far, and electrical and optical signals can travel only so fast.

The word “cluster” is often used for small to moderate scale HPC resources less impressive than the Top-500. Clusters are often maintained in computing centers that support several such systems, all sharing common networking and storage to support common compute intensive tasks.

Logging In

The first step in using a cluster is to establish a connection from our laptop to the cluster. When we are sitting at a computer (or standing, or holding it in our hands or on our wrists), we have come to expect a visual display with icons, widgets, and perhaps some windows or applications: a graphical user interface, or GUI. Since computer clusters are remote resources that we connect to over often slow or laggy interfaces (WiFi and VPNs especially), it is more practical to use a command-line interface, or CLI, in which commands and results are transmitted via text, only. Anything other than text (images, for example) must be written to disk and opened with a separate program.

If you have ever opened the Windows Command Prompt or macOS Terminal, you have seen a CLI. If you have already taken The Carpentries’ courses on the UNIX Shell or Version Control, you have used the CLI on your local machine somewhat extensively. The only leap to be made here is to open a CLI on a remote machine, while taking some precautions so that other folks on the network can’t see (or change) the commands you’re running or the results the remote machine sends back. We will use the Secure SHell protocol (or SSH) to open an encrypted network connection between two machines, allowing you to send & receive text and data without having to worry about prying eyes.

Make sure you have a SSH client installed on your laptop. Refer to the

setup section for more details. SSH clients are

usually command-line tools, where you provide the remote machine address as the

only required argument. If your username on the remote system differs from what

you use locally, you must provide that as well. If your SSH client has a

graphical front-end, such as PuTTY or MobaXterm, you will set these arguments

before clicking “connect.” From the terminal, you’ll write something like ssh

userName@hostname, where the “@” symbol is used to separate the two parts of a

single argument.

Go ahead and open your terminal or graphical SSH client, then log in to the cluster using your username and the remote computer you can reach from the outside world, University of Waterloo.

[user@laptop ~]$ ssh yourUsername@graham.computecanada.ca

Remember to replace yourUsername with your username or the one

supplied by the instructors. You may be asked for your password. Watch out: the

characters you type after the password prompt are not displayed on the screen.

Normal output will resume once you press Enter.

Where Are We?

Very often, many users are tempted to think of a high-performance computing

installation as one giant, magical machine. Sometimes, people will assume that

the computer they’ve logged onto is the entire computing cluster. So what’s

really happening? What computer have we logged on to? The name of the current

computer we are logged onto can be checked with the hostname command. (You

may also notice that the current hostname is also part of our prompt!)

[yourUsername@gra-login1 ~]$ hostname

gra-login1

What’s in Your Home Directory?

The system administrators may have configured your home directory with some helpful files, folders, and links (shortcuts) to space reserved for you on other filesystems. Take a look around and see what you can find.

Hint: The shell commands

pwdandlsmay come in handy.Home directory contents vary from user to user. Please discuss any differences you spot with your neighbors:

It’s a Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood

The deepest layer should differ: yourUsername is uniquely yours. Are there differences in the path at higher levels?

If both of you have empty directories, they will look identical. If you or your neighbor has used the system before, there may be differences. What are you working on?

Solution

Use

pwdto print the working directory path:[yourUsername@gra-login1 ~]$ pwdYou can run

lsto list the directory contents, though it’s possible nothing will show up (if no files have been provided). To be sure, use the-aflag to show hidden files, too.[yourUsername@gra-login1 ~]$ ls -aAt a minimum, this will show the current directory as

., and the parent directory as...

Nodes

Individual computers that compose a cluster are typically called nodes (although you will also hear people call them servers, computers and machines). On a cluster, there are different types of nodes for different types of tasks. The node where you are right now is called the head node, login node, landing pad, or submit node. A login node serves as an access point to the cluster.

As a gateway, it is well suited for uploading and downloading files, setting up software, and running quick tests. Generally speaking, the login node should not be used for time-consuming or resource-intensive tasks. You should be alert to this, and check with your site’s operators or documentation for details of what is and isn’t allowed. In these lessons, we will avoid running jobs on the head node.

Dedicated Transfer Nodes

If you want to transfer larger amounts of data to or from the cluster, some systems offer dedicated nodes for data transfers only. The motivation for this lies in the fact that larger data transfers should not obstruct operation of the login node for anybody else. Check with your cluster’s documentation or its support team if such a transfer node is available. As a rule of thumb, consider all transfers of a volume larger than 500 MB to 1 GB as large. But these numbers change, e.g., depending on the network connection of yourself and of your cluster or other factors.

The real work on a cluster gets done by the worker (or compute) nodes. Worker nodes come in many shapes and sizes, but generally are dedicated to long or hard tasks that require a lot of computational resources.

All interaction with the worker nodes is handled by a specialized piece of software called a scheduler (the scheduler used in this lesson is called ). We’ll learn more about how to use the scheduler to submit jobs next, but for now, it can also tell us more information about the worker nodes.

For example, we can view all of the worker nodes by running the command

sinfo.

[yourUsername@gra-login1 ~]$ sinfo

PARTITION AVAIL TIMELIMIT NODES STATE NODELIST

compute* up 7-00:00:00 1 drain* gra259

compute* up 7-00:00:00 11 down* gra[8,99,211,268,376,635,647,803,85...

compute* up 7-00:00:00 1 drng gra272

compute* up 7-00:00:00 31 comp gra[988-991,994-1002,1006-1007,1015...

compute* up 7-00:00:00 33 drain gra[225-251,253-256,677,1026]

compute* up 7-00:00:00 323 mix gra[7,13,25,41,43-44,56,58-77,107-1...

compute* up 7-00:00:00 464 alloc gra[1-6,9-12,14-19,21-24,26-40,42,4...

compute* up 7-00:00:00 176 idle gra[78-98,123-124,128-162,170-172,2...

compute* up 7-00:00:00 3 down gra[20,801,937]

There are also specialized machines used for managing disk storage, user authentication, and other infrastructure-related tasks. Although we do not typically logon to or interact with these machines directly, they enable a number of key features like ensuring our user account and files are available throughout the HPC system.

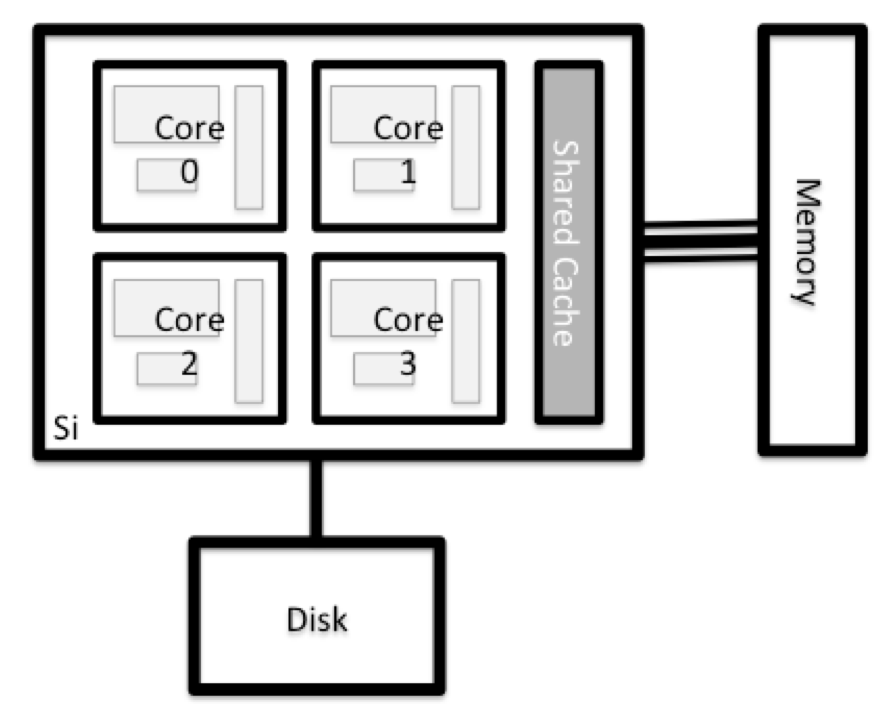

What’s in a Node?

All of the nodes in an HPC system have the same components as your own laptop or desktop: CPUs (sometimes also called processors or cores), memory (or RAM), and disk space. CPUs are a computer’s tool for actually running programs and calculations. Information about a current task is stored in the computer’s memory. Disk refers to all storage that can be accessed like a file system. This is generally storage that can hold data permanently, i.e. data is still there even if the computer has been restarted. While this storage can be local (a hard drive installed inside of it), it is more common for nodes to connect to a shared, remote fileserver or cluster of servers.

Explore Your Computer

Try to find out the number of CPUs and amount of memory available on your personal computer.

Note that, if you’re logged in to the remote computer cluster, you need to log out first. To do so, type

Ctrl+dorexit:[yourUsername@gra-login1 ~]$ exit [user@laptop ~]$Solution

There are several ways to do this. Most operating systems have a graphical system monitor, like the Windows Task Manager. More detailed information can be found on the command line:

- Run system utilities

[user@laptop ~]$ nproc --all [user@laptop ~]$ free -m- Read from

/proc[user@laptop ~]$ cat /proc/cpuinfo [user@laptop ~]$ cat /proc/meminfo- Run system monitor

[user@laptop ~]$ htop

Explore the Head Node

Now compare the resources of your computer with those of the head node.

Solution

[user@laptop ~]$ ssh yourUsername@graham.computecanada.ca [yourUsername@gra-login1 ~]$ nproc --all [yourUsername@gra-login1 ~]$ free -mYou can get more information about the processors using

lscpu, and a lot of detail about the memory by reading the file/proc/meminfo:[yourUsername@gra-login1 ~]$ less /proc/meminfoYou can also explore the available filesystems using

dfto show disk free space. The-hflag renders the sizes in a human-friendly format, i.e., GB instead of B. The type flag-Tshows what kind of filesystem each resource is.[yourUsername@gra-login1 ~]$ df -ThThe local filesystems (ext, tmp, xfs, zfs) will depend on whether you’re on the same login node (or compute node, later on). Networked filesystems (beegfs, cifs, gpfs, nfs, pvfs) will be similar — but may include yourUsername, depending on how it is mounted.

Shared Filesystems

This is an important point to remember: files saved on one node (computer) are often available everywhere on the cluster!

Explore a Worker Node

Finally, let’s look at the resources available on the worker nodes where your jobs will actually run. Try running this command to see the name, CPUs and memory available on the worker nodes:

[yourUsername@gra-login1 ~]$ sinfo -n aci-377 -o "%n %c %m"

Compare Your Computer, the Head Node and the Worker Node

Compare your laptop’s number of processors and memory with the numbers you see on the cluster head node and worker node. Discuss the differences with your neighbor.

What implications do you think the differences might have on running your research work on the different systems and nodes?

Differences Between Nodes

Many HPC clusters have a variety of nodes optimized for particular workloads. Some nodes may have larger amount of memory, or specialized resources such as Graphical Processing Units (GPUs).

With all of this in mind, we will now cover how to talk to the cluster’s scheduler, and use it to start running our scripts and programs!

Key Points

An HPC system is a set of networked machines.

HPC systems typically provide login nodes and a set of worker nodes.

The resources found on independent (worker) nodes can vary in volume and type (amount of RAM, processor architecture, availability of network mounted filesystems, etc.).

Files saved on one node are available on all nodes.