Content from Introduction

Last updated on 2025-03-18 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What sort of scientific questions can we answer with image processing / computer vision?

- What are morphometric problems?

Objectives

- Recognise scientific questions that could be solved with image processing / computer vision.

- Recognise morphometric problems (those dealing with the number, size, or shape of the objects in an image).

As computer systems have become faster and more powerful, and cameras and other imaging systems have become commonplace in many other areas of life, the need has grown for researchers to be able to process and analyse image data. Considering the large volumes of data that can be involved - high-resolution images that take up a lot of disk space/virtual memory, and/or collections of many images that must be processed together - and the time-consuming and error-prone nature of manual processing, it can be advantageous or even necessary for this processing and analysis to be automated as a computer program.

This lesson introduces an open source toolkit for processing image

data: the Python programming language and the scikit-image

(skimage) library. With careful experimental design,

Python code can be a powerful instrument in answering many different

kinds of questions.

Uses of Image Processing in Research

Automated processing can be used to analyse many different properties of an image, including the distribution and change in colours in the image, the number, size, position, orientation, and shape of objects in the image, and even - when combined with machine learning techniques for object recognition - the type of objects in the image.

Some examples of image processing methods applied in research include:

- Imaging a black hole

- Segmentation of liver and vessels from CT images

- Monitoring wading birds in the Everglades using drones (Blog article summarizing the paper)

- Estimating the population of emperor penguins

- Global-scale analysis of marine plankton diversity

With this lesson, we aim to provide a thorough grounding in the fundamental concepts and skills of working with image data in Python. Most of the examples used in this lesson focus on one particular class of image processing technique, morphometrics, but what you will learn can be used to solve a much wider range of problems.

Morphometrics

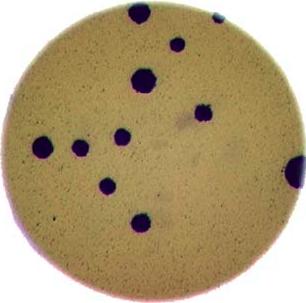

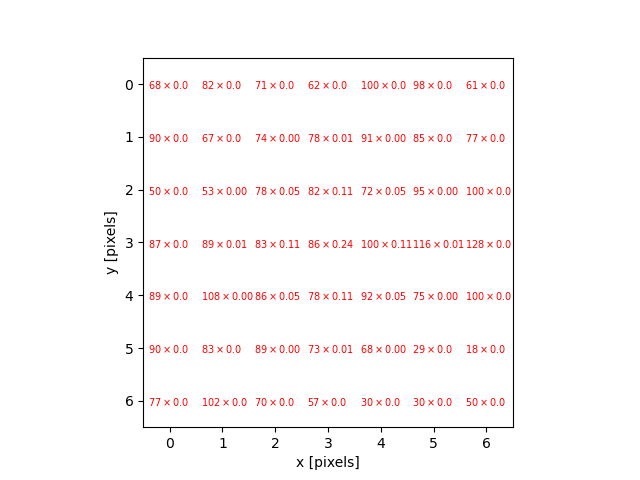

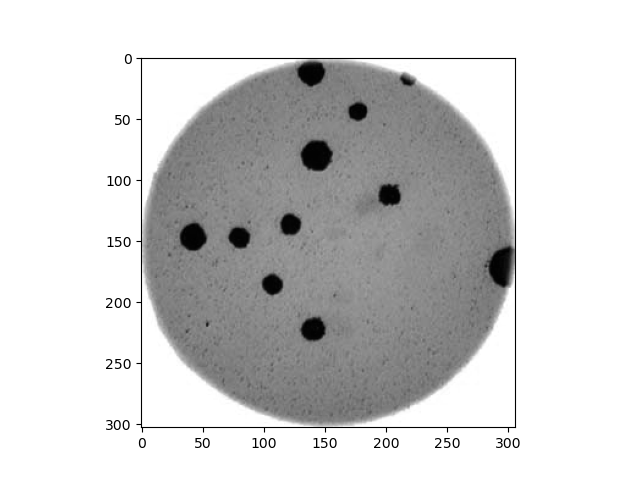

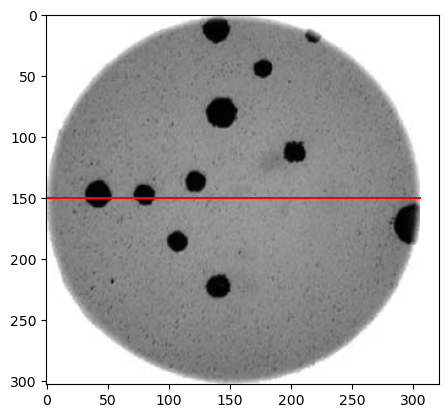

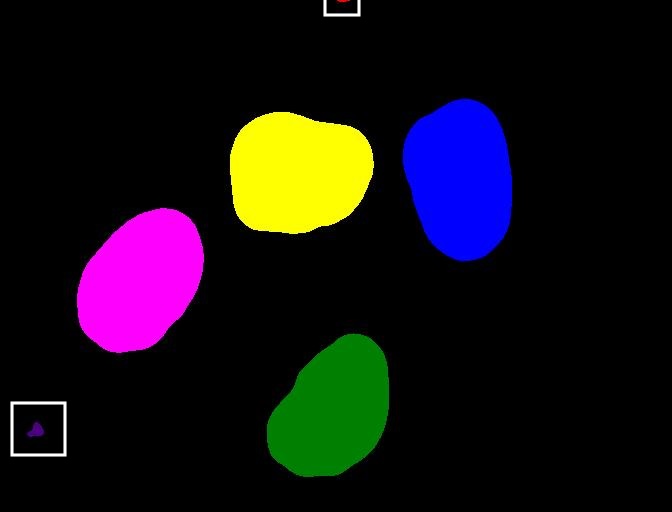

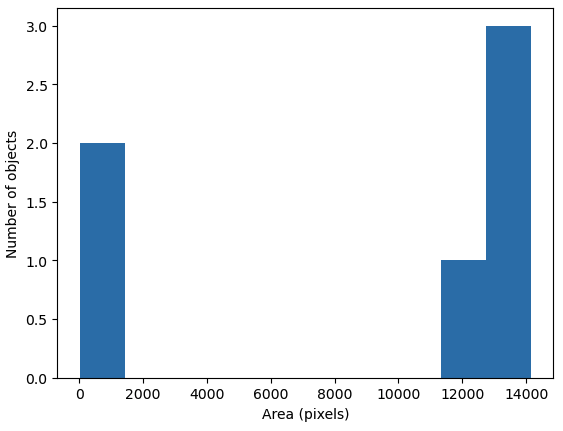

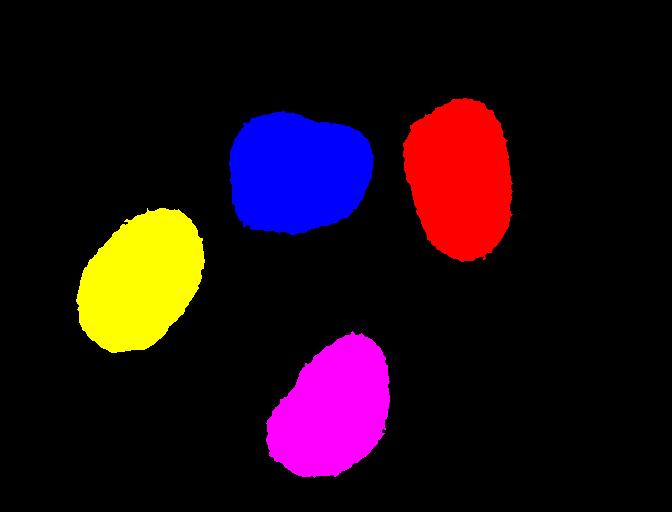

Morphometrics involves counting the number of objects in an image, analyzing the size of the objects, or analyzing the shape of the objects. For example, we might be interested in automatically counting the number of bacterial colonies growing in a Petri dish, as shown in this image:

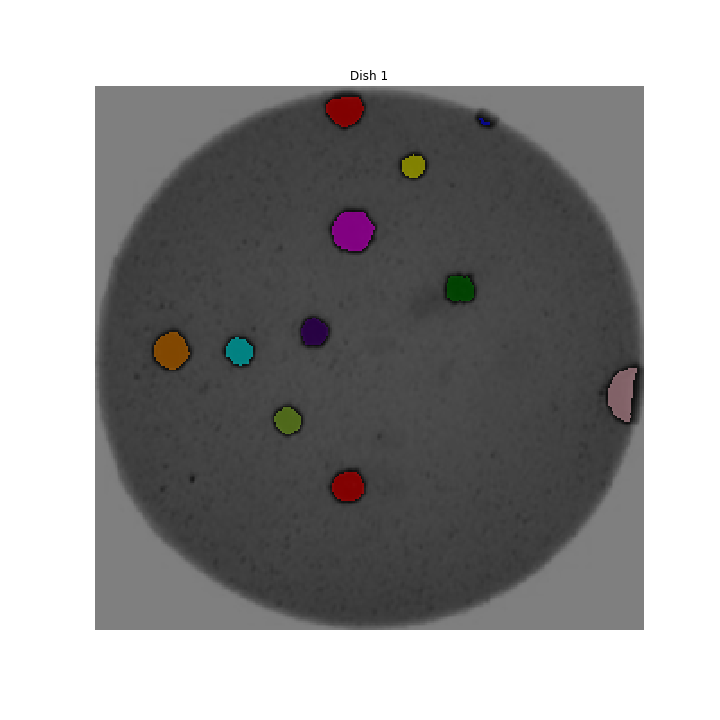

We could use image processing to find the colonies, count them, and then highlight their locations on the original image, resulting in an image like this:

Why write a program to do that?

Note that you can easily manually count the number of bacteria colonies shown in the morphometric example above. Why should we learn how to write a Python program to do a task we could easily perform with our own eyes? There are at least two reasons to learn how to perform tasks like these with Python and scikit-image:

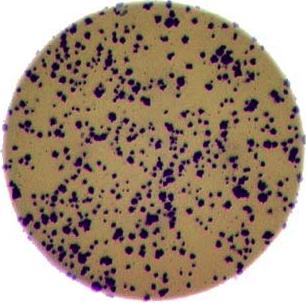

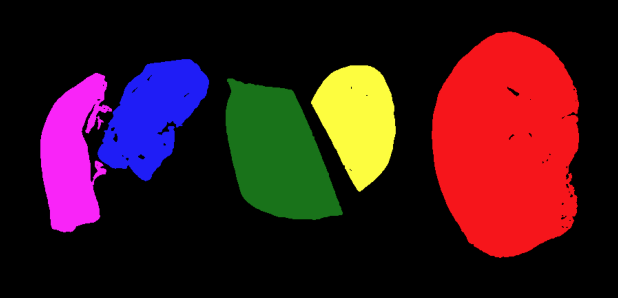

- What if there are many more bacteria colonies in the Petri dish? For example, suppose the image looked like this:

Manually counting the colonies in that image would present more of a challenge. A Python program using scikit-image could count the number of colonies more accurately, and much more quickly, than a human could.

- What if you have hundreds, or thousands, of images to consider? Imagine having to manually count colonies on several thousand images like those above. A Python program using scikit-image could move through all of the images in seconds; how long would a graduate student require to do the task? Which process would be more accurate and repeatable?

As you can see, the simple image processing / computer vision techniques you will learn during this workshop can be very valuable tools for scientific research.

As we move through this workshop, we will learn image analysis methods useful for many different scientific problems. These will be linked together and applied to a real problem in the final end-of-workshop capstone challenge.

Let’s get started, by learning some basics about how images are represented and stored digitally.

- Simple Python and scikit-image techniques can be used to solve genuine image analysis problems.

- Morphometric problems involve the number, shape, and / or size of the objects in an image.

Content from Image Basics

Last updated on 2025-03-18 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How are images represented in digital format?

Objectives

- Define the terms bit, byte, kilobyte, megabyte, etc.

- Explain how a digital image is composed of pixels.

- Recommend using imageio (resp. scikit-image) for I/O (resp. image processing) tasks.

- Explain how images are stored in NumPy arrays.

- Explain the left-hand coordinate system used in digital images.

- Explain the RGB additive colour model used in digital images.

- Explain the order of the three colour values in scikit-image images.

- Explain the characteristics of the BMP, JPEG, and TIFF image formats.

- Explain the difference between lossy and lossless compression.

- Explain the advantages and disadvantages of compressed image formats.

- Explain what information could be contained in image metadata.

The images we see on hard copy, view with our electronic devices, or process with our programs are represented and stored in the computer as numeric abstractions, approximations of what we see with our eyes in the real world. Before we begin to learn how to process images with Python programs, we need to spend some time understanding how these abstractions work.

Feel free to make use of the available cheat-sheet as a guide for the rest of the course material. View it online, share it, or print the PDF!

Pixels

It is important to realise that images are stored as rectangular arrays of hundreds, thousands, or millions of discrete “picture elements,” otherwise known as pixels. Each pixel can be thought of as a single square point of coloured light.

For example, consider this image of a maize seedling, with a square area designated by a red box:

Now, if we zoomed in close enough to see the pixels in the red box, we would see something like this:

Note that each square in the enlarged image area - each pixel - is all one colour, but that each pixel can have a different colour from its neighbors. Viewed from a distance, these pixels seem to blend together to form the image we see.

Real-world images are typically made up of a vast number of pixels, and each of these pixels is one of potentially millions of colours. While we will deal with pictures of such complexity in this lesson, let’s start our exploration with just 15 pixels in a 5 x 3 matrix with 2 colours, and work our way up to that complexity.

Matrices, arrays, images and pixels

A matrix is a mathematical concept - numbers evenly arranged in a rectangle. This can be a two-dimensional rectangle, like the shape of the screen you’re looking at now. Or it could be a three-dimensional equivalent, a cuboid, or have even more dimensions, but always keeping the evenly spaced arrangement of numbers. In computing, an array refers to a structure in the computer’s memory where data is stored in evenly spaced elements. This is strongly analogous to a matrix. A NumPy array is a type of variable (a simpler example of a type is an integer). For our purposes, the distinction between matrices and arrays is not important, we don’t really care how the computer arranges our data in its memory. The important thing is that the computer stores values describing the pixels in images, as arrays. And the terms matrix and array will be used interchangeably.

Loading images

As noted, images we want to analyze (process) with Python are loaded into arrays. There are multiple ways to load images. In this lesson, we use imageio, a Python library for reading (loading) and writing (saving) image data, and more specifically its version 3. But, really, we could use any image loader which would return a NumPy array.

The v3 module of imageio (imageio.v3) is

imported as iio (see note in the next section). Version 3

of imageio has the benefit of supporting nD (multidimensional) image

data natively (think of volumes, movies).

Let us load our image data from disk using the imread

function from the imageio.v3 module.

OUTPUT

<class 'numpy.ndarray'>Note that, using the same image loader or a different one, we could also read in remotely hosted data.

Why not use

skimage.io.imread()?

The scikit-image library has its own function to read an image, so

you might be asking why we don’t use it here. Actually,

skimage.io.imread() uses iio.imread()

internally when loading an image into Python. It is certainly something

you may use as you see fit in your own code. In this lesson, we use the

imageio library to read or write images, while scikit-image is dedicated

to performing operations on the images. Using imageio gives us more

flexibility, especially when it comes to handling metadata.

Beyond NumPy arrays

Beyond NumPy arrays, there exist other types of variables which are

array-like. Notably, pandas.DataFrame

and xarray.DataArray

can hold labeled, tabular data. These are not natively supported in

scikit-image, the scientific toolkit we use in this lesson for

processing image data. However, data stored in these types can be

converted to numpy.ndarray with certain assumptions (see

pandas.DataFrame.to_numpy() and

xarray.DataArray.data). Particularly, these conversions

ignore the sampling coordinates (DataFrame.index,

DataFrame.columns, or DataArray.coords), which

may result in misrepresented data, for instance, when the original data

points are irregularly spaced.

Working with pixels

First, let us add the necessary imports:

PYTHON

"""Python libraries for learning and performing image processing."""

import ipympl

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import skimage as skiImport statements in Python

In Python, the import statement is used to load

additional functionality into a program. This is necessary when we want

our code to do something more specialised, which cannot easily be

achieved with the limited set of basic tools and data structures

available in the default Python environment.

Additional functionality can be loaded as a single function or

object, a module defining several of these, or a library containing many

modules. You will encounter several different forms of

import statement.

PYTHON

import skimage # form 1, load whole skimage library

import skimage.draw # form 2, load skimage.draw module only

from skimage.draw import disk # form 3, load only the disk function

import skimage as ski # form 4, load all of skimage into an object called skiIn the example above, form 1 loads the entire scikit-image library

into the program as an object. Individual modules of the library are

then available within that object, e.g., to access the disk

function used in the drawing episode, you

would write skimage.draw.disk().

Form 2 loads only the draw module of

skimage into the program. The syntax needed to use the

module remains unchanged: to access the disk function, we

would use the same function call as given for form 1.

Form 3 can be used to import only a specific function/class from a

library/module. Unlike the other forms, when this approach is used, the

imported function or class can be called by its name only, without

prefixing it with the name of the library/module from which it was

loaded, i.e., disk() instead of

skimage.draw.disk() using the example above. One hazard of

this form is that importing like this will overwrite any object with the

same name that was defined/imported earlier in the program, i.e., the

example above would replace any existing object called disk

with the disk function from skimage.draw.

Finally, the as keyword can be used when importing, to

define a name to be used as shorthand for the library/module being

imported. This name is referred to as an alias. Typically, using an

alias (such as np for the NumPy library) saves us a little

typing. You may see as combined with any of the other first

three forms of import statements.

Which form is used often depends on the size and number of additional tools being loaded into the program.

Now that we have our libraries loaded, we will run a Jupyter Magic Command that will ensure our images display in our Jupyter document with pixel information that will help us more efficiently run commands later in the session.

With that taken care of, let us display the image we have loaded,

using the imshow function from the

matplotlib.pyplot module.

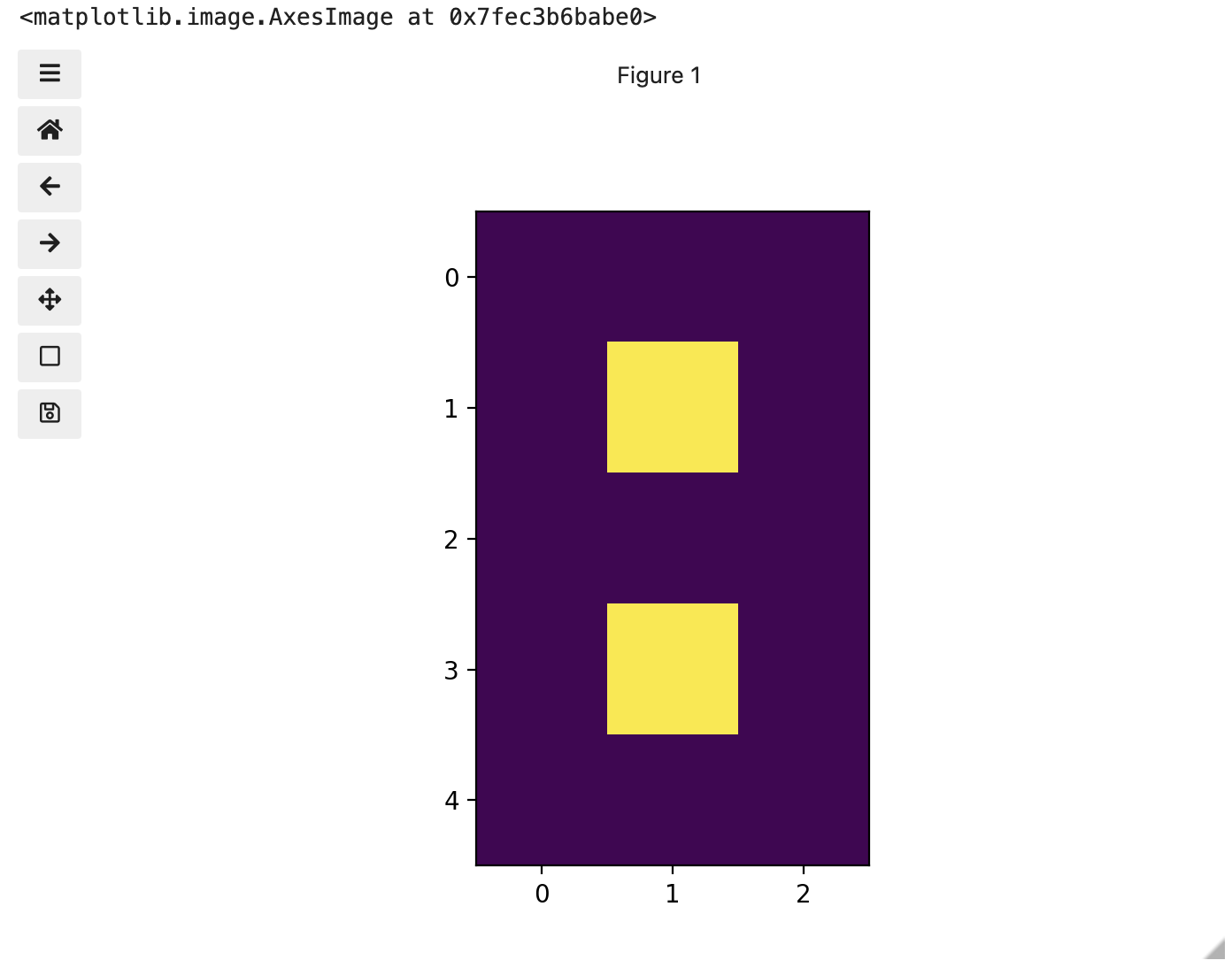

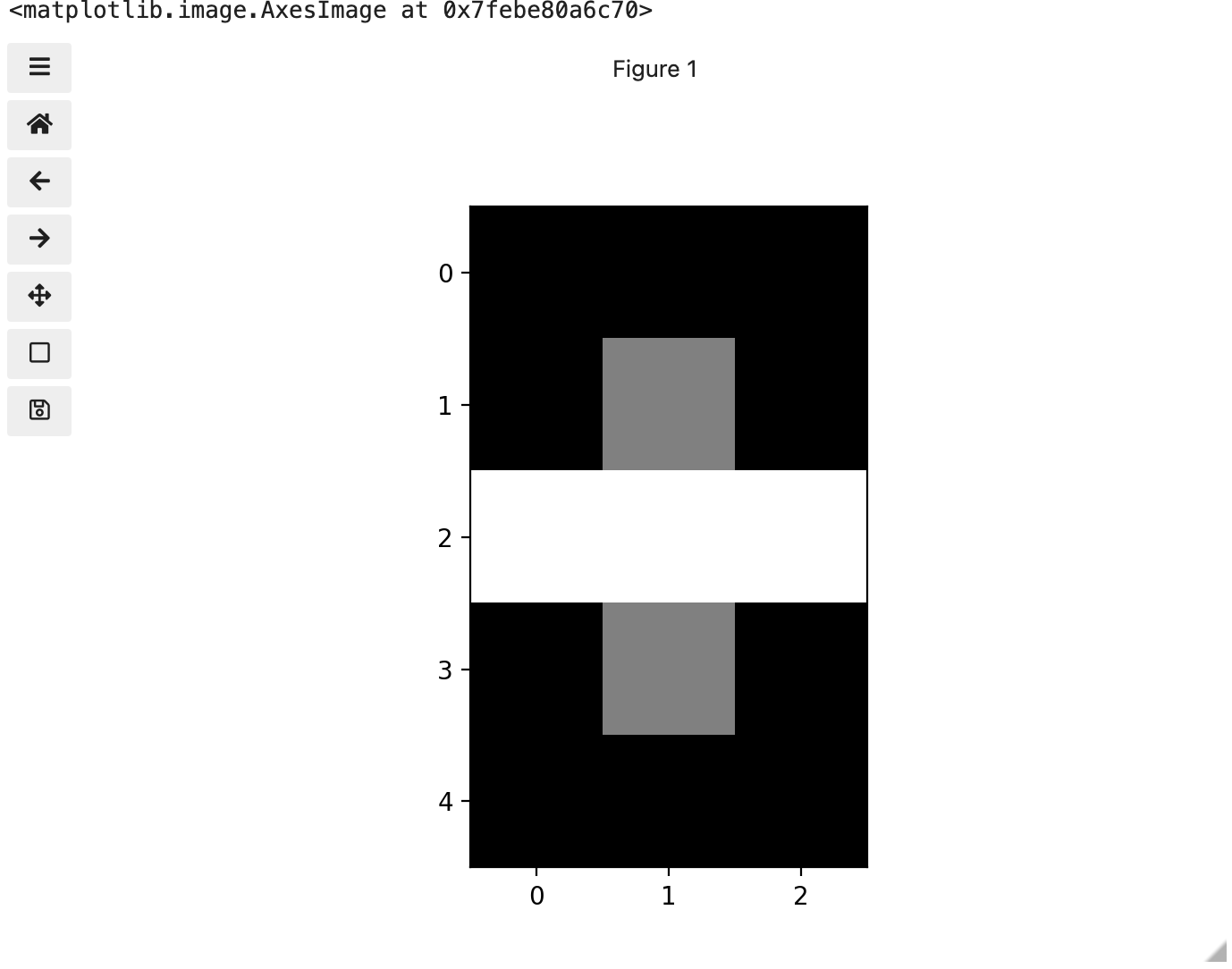

You might be thinking, “That does look vaguely like an eight, and I see two colours but how can that be only 15 pixels”. The display of the eight you see does use a lot more screen pixels to display our eight so large, but that does not mean there is information for all those screen pixels in the file. All those extra pixels are a consequence of our viewer creating additional pixels through interpolation. It could have just displayed it as a tiny image using only 15 screen pixels if the viewer was designed differently.

While many image file formats contain descriptive metadata that can

be essential, the bulk of a picture file is just arrays of numeric

information that, when interpreted according to a certain rule set,

become recognizable as an image to us. Our image of an eight is no

exception, and imageio.v3 stored that image data in an

array of arrays making a 5 x 3 matrix of 15 pixels. We can demonstrate

that by calling on the shape property of our image variable and see the

matrix by printing our image variable to the screen.

OUTPUT

(5, 3)

[[0. 0. 0.]

[0. 1. 0.]

[0. 0. 0.]

[0. 1. 0.]

[0. 0. 0.]]Thus if we have tools that will allow us to manipulate these arrays

of numbers, we can manipulate the image. The NumPy library can be

particularly useful here, so let’s try that out using NumPy array

slicing. Notice that the default behavior of the imshow

function appended row and column numbers that will be helpful to us as

we try to address individual or groups of pixels. First let’s load

another copy of our eight, and then make it look like a zero.

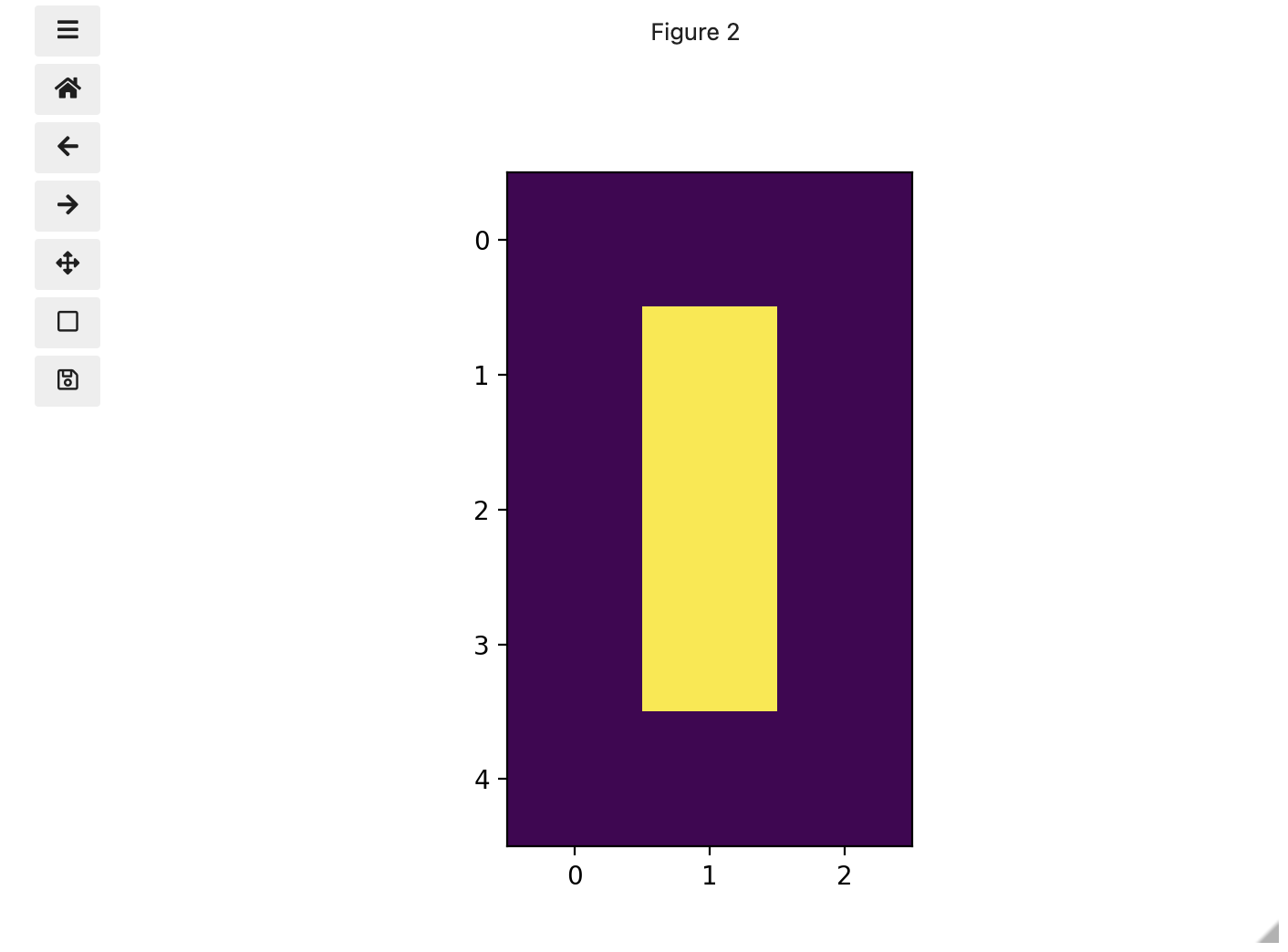

To make it look like a zero, we need to change the number underlying the centremost pixel to be 1. With the help of those row and column headers, at this small scale we can determine the centre pixel is in row labeled 2 and column labeled 1. Using array slicing, we can then address and assign a new value to that position.

PYTHON

zero = iio.imread(uri="data/eight.tif")

zero[2, 1]= 1.0

# The following line of code creates a new figure for imshow to use in displaying our output.

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.imshow(zero)

print(zero)OUTPUT

[[0. 0. 0.]

[0. 1. 0.]

[0. 1. 0.]

[0. 1. 0.]

[0. 0. 0.]]

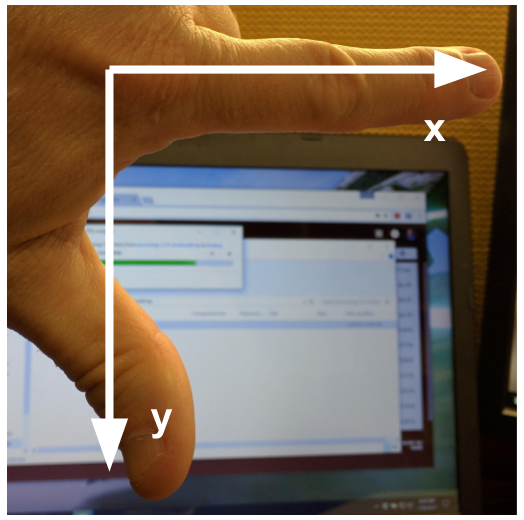

Coordinate system

When we process images, we can access, examine, and / or change the colour of any pixel we wish. To do this, we need some convention on how to access pixels individually; a way to give each one a name, or an address of a sort.

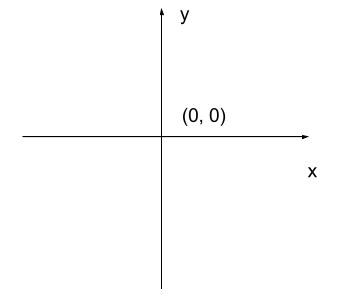

The most common manner to do this, and the one we will use in our programs, is to assign a modified Cartesian coordinate system to the image. The coordinate system we usually see in mathematics has a horizontal x-axis and a vertical y-axis, like this:

The modified coordinate system used for our images will have only positive coordinates, the origin will be in the upper left corner instead of the centre, and y coordinate values will get larger as they go down instead of up, like this:

This is called a left-hand coordinate system. If you hold your left hand in front of your face and point your thumb at the floor, your extended index finger will correspond to the x-axis while your thumb represents the y-axis.

Until you have worked with images for a while, the most common mistake that you will make with coordinates is to forget that y coordinates get larger as they go down instead of up as in a normal Cartesian coordinate system. Consequently, it may be helpful to think in terms of counting down rows (r) for the y-axis and across columns (c) for the x-axis. This can be especially helpful in cases where you need to transpose image viewer data provided in x,y format to y,x format. Thus, we will use cx and ry where appropriate to help bridge these two approaches.

Changing Pixel Values (5 min)

Load another copy of eight named five, and then change the value of pixels so you have what looks like a 5 instead of an 8. Display the image and print out the matrix as well.

More colours

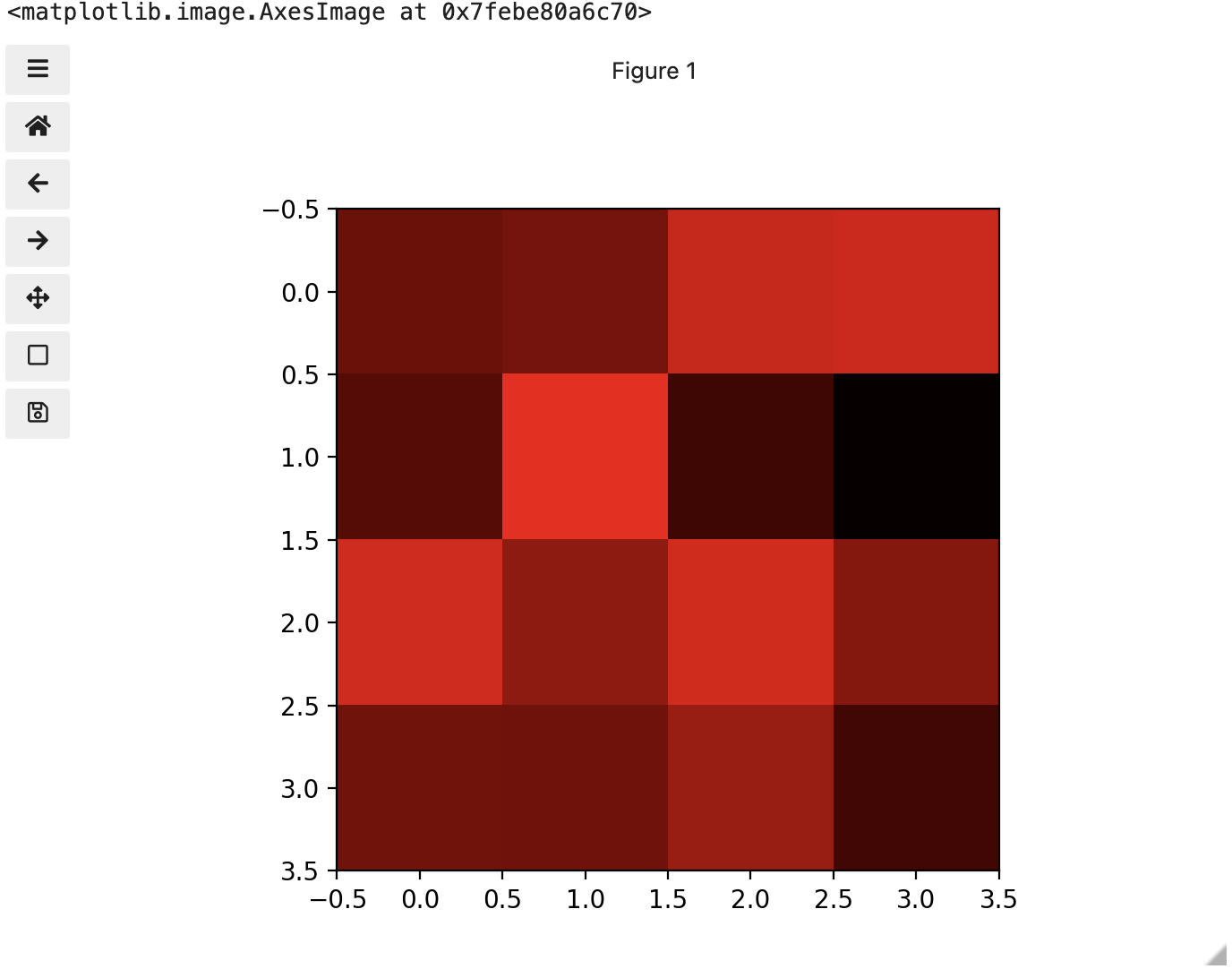

Up to now, we only had a 2 colour matrix, but we can have more if we use other numbers or fractions. One common way is to use the numbers between 0 and 255 to allow for 256 different colours or 256 different levels of grey. Let’s try that out.

PYTHON

# make a copy of eight

three_colours = iio.imread(uri="data/eight.tif")

# multiply the whole matrix by 128

three_colours = three_colours * 128

# set the middle row (index 2) to the value of 255.,

# so you end up with the values 0., 128., and 255.

three_colours[2, :] = 255.

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.imshow(three_colours)

print(three_colours)

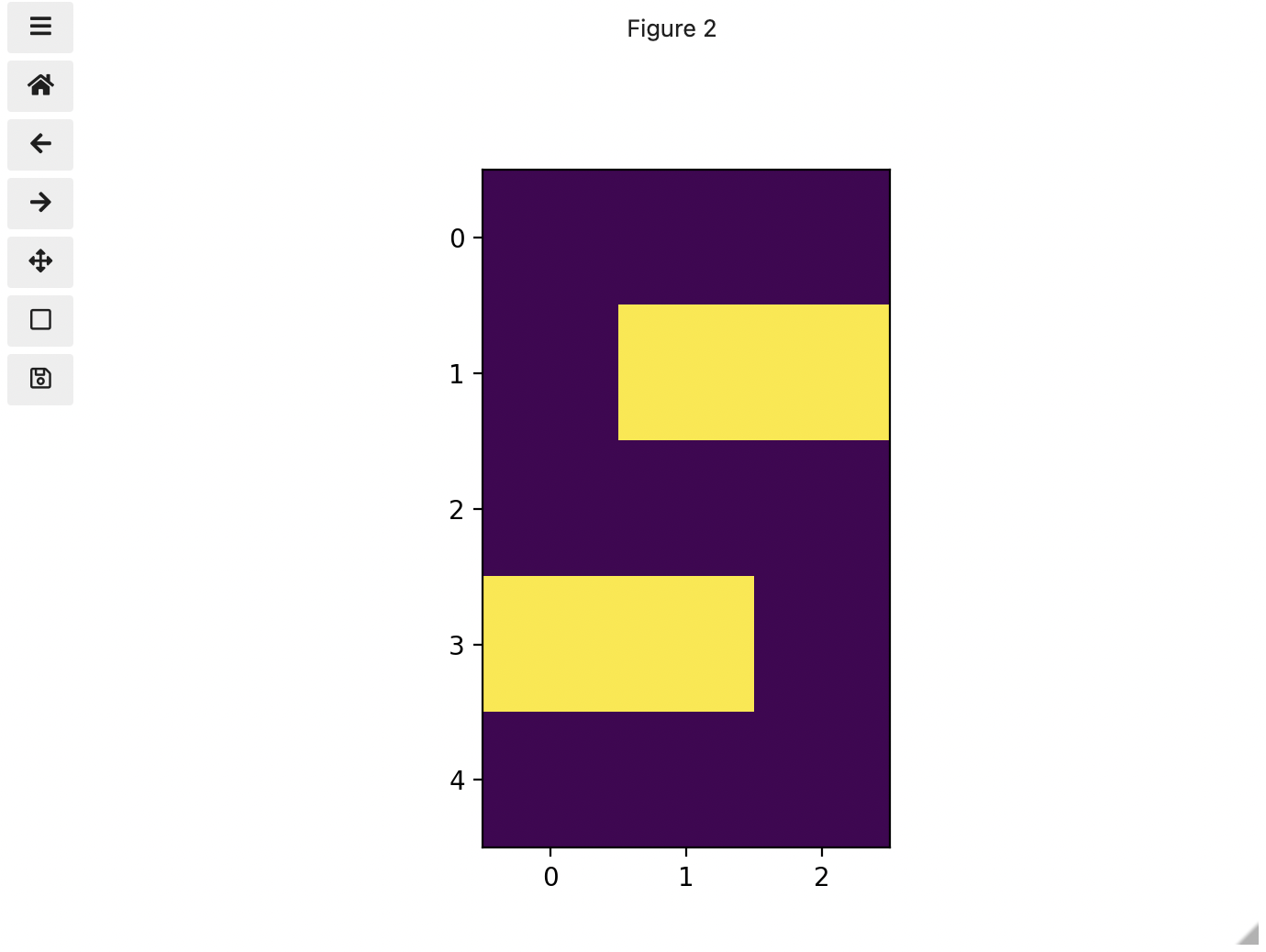

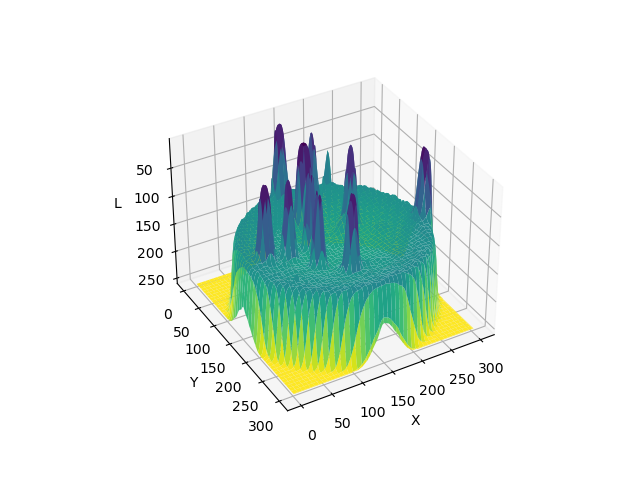

We now have 3 colours, but are they the three colours you expected? They all appear to be on a continuum of dark purple on the low end and yellow on the high end. This is a consequence of the default colour map (cmap) in this library. You can think of a colour map as an association or mapping of numbers to a specific colour. However, the goal here is not to have one number for every possible colour, but rather to have a continuum of colours that demonstrate relative intensity. In our specific case here for example, 255 or the highest intensity is mapped to yellow, and 0 or the lowest intensity is mapped to a dark purple. The best colour map for your data will vary and there are many options built in, but this default selection was not arbitrary. A lot of science went into making this the default due to its robustness when it comes to how the human mind interprets relative colour values, grey-scale printability, and colour-blind friendliness (You can read more about this default colour map in a Matplotlib tutorial and an explanatory article by the authors). Thus it is a good place to start, and you should change it only with purpose and forethought. For now, let’s see how you can do that using an alternative map you have likely seen before where it will be even easier to see it as a mapped continuum of intensities: greyscale.

Above we have exactly the same underlying data matrix, but in greyscale. Zero maps to black, 255 maps to white, and 128 maps to medium grey. Here we only have a single channel in the data and utilize a grayscale color map to represent the luminance, or intensity of the data and correspondingly this channel is referred to as the luminance channel.

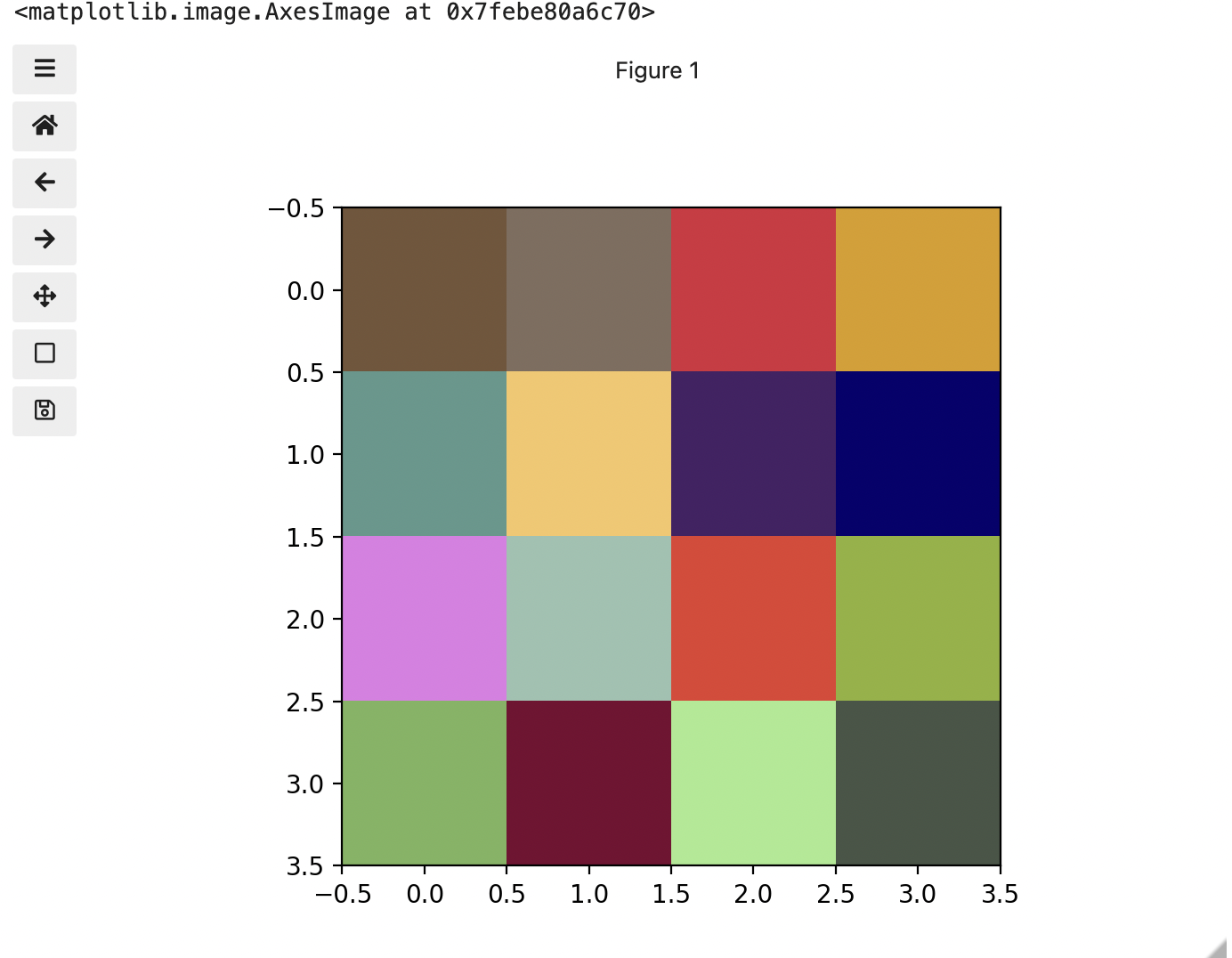

Even more colours

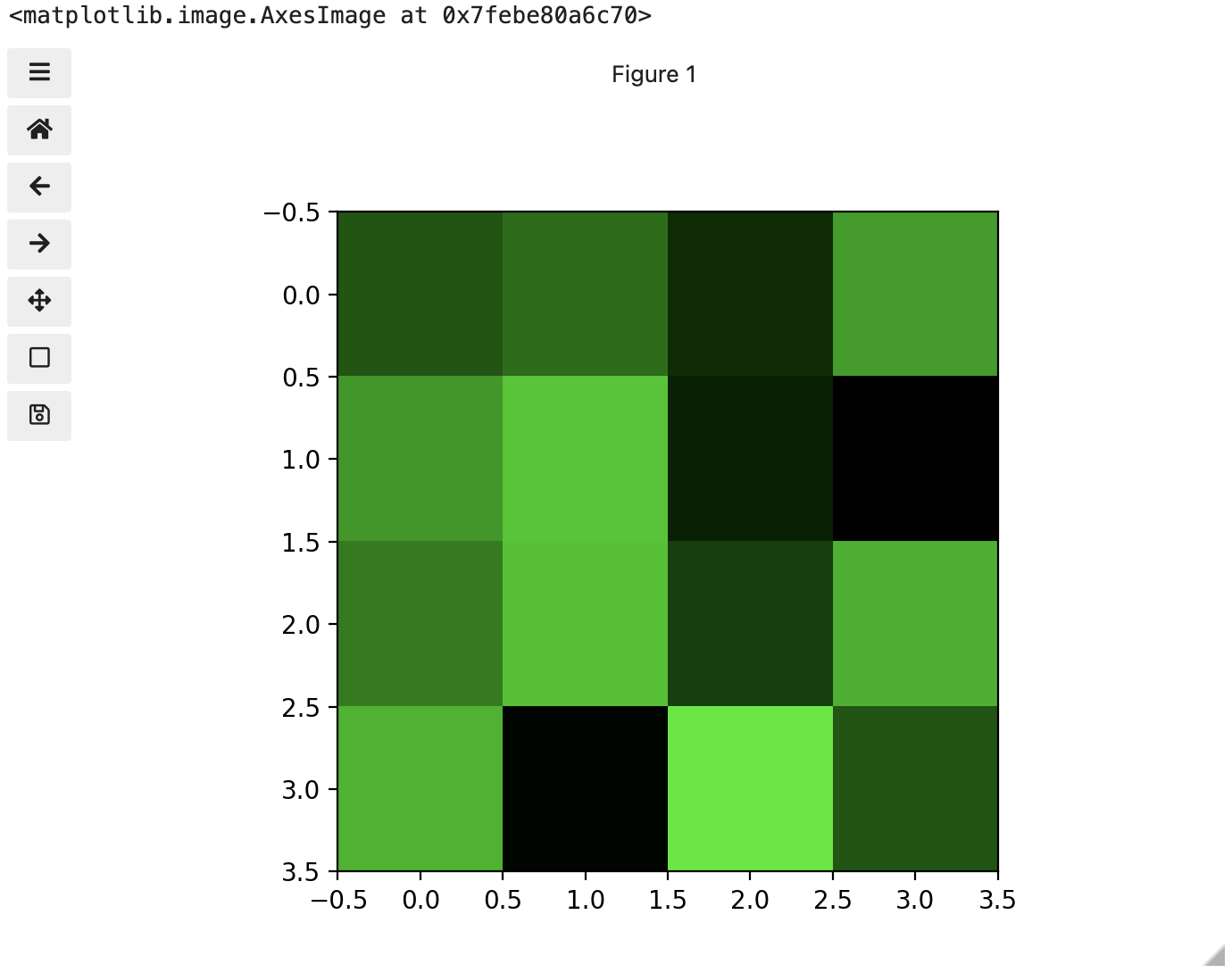

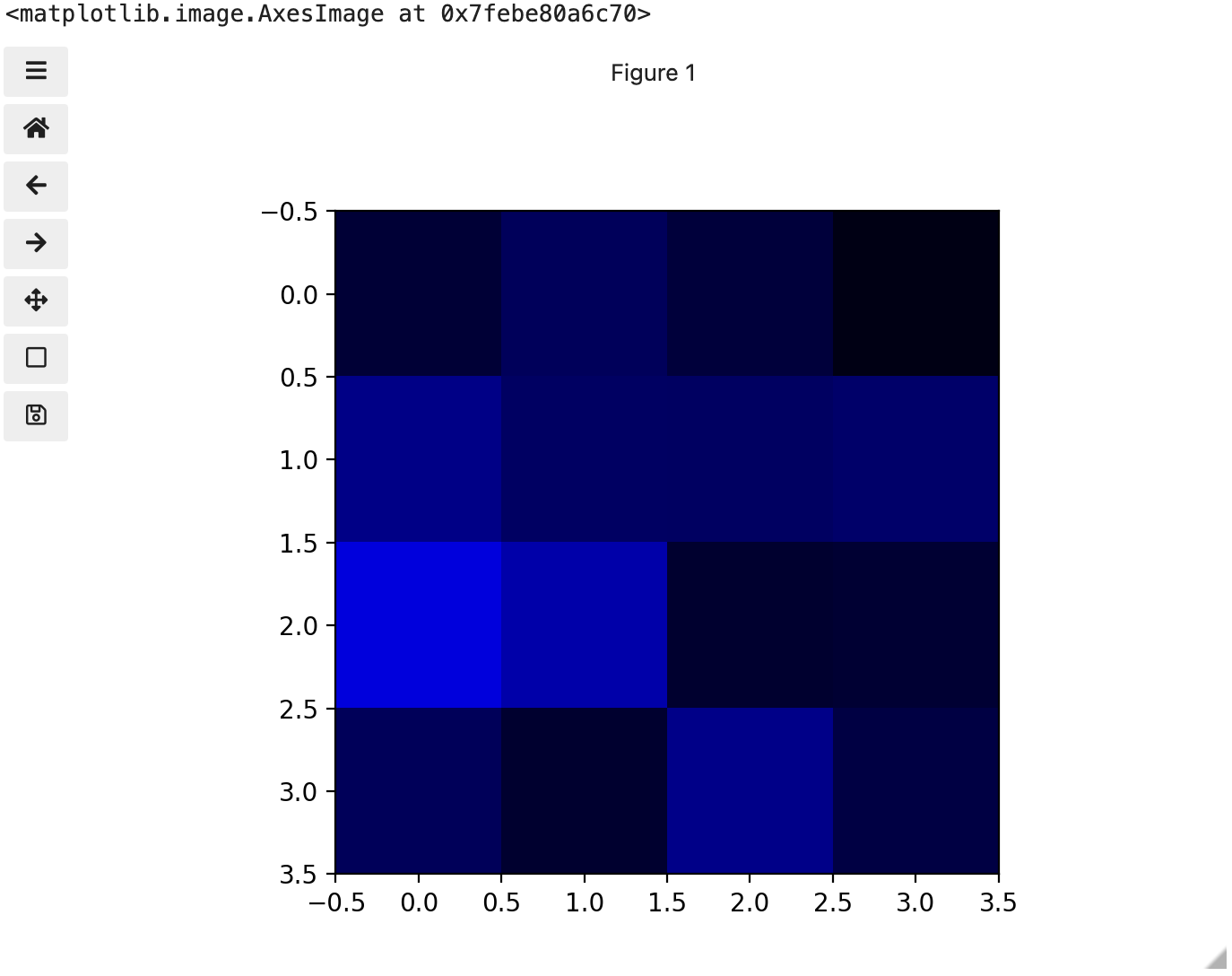

This is all well and good at this scale, but what happens when we instead have a picture of a natural landscape that contains millions of colours. Having a one to one mapping of number to colour like this would be inefficient and make adjustments and building tools to do so very difficult. Rather than larger numbers, the solution is to have more numbers in more dimensions. Storing the numbers in a multi-dimensional matrix where each colour or property like transparency is associated with its own dimension allows for individual contributions to a pixel to be adjusted independently. This ability to manipulate properties of groups of pixels separately will be key to certain techniques explored in later chapters of this lesson. To get started let’s see an example of how different dimensions of information combine to produce a set of pixels using a 4 x 4 matrix with 3 dimensions for the colours red, green, and blue. Rather than loading it from a file, we will generate this example using NumPy.

PYTHON

# set the random seed so we all get the same matrix

pseudorandomizer = np.random.RandomState(2021)

# create a 4 × 4 checkerboard of random colours

checkerboard = pseudorandomizer.randint(0, 255, size=(4, 4, 3))

# restore the default map as you show the image

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.imshow(checkerboard)

# display the arrays

print(checkerboard)OUTPUT

[[[116 85 57]

[128 109 94]

[214 44 62]

[219 157 21]]

[[ 93 152 140]

[246 198 102]

[ 70 33 101]

[ 7 1 110]]

[[225 124 229]

[154 194 176]

[227 63 49]

[144 178 54]]

[[123 180 93]

[120 5 49]

[166 234 142]

[ 71 85 70]]]

Previously we had one number being mapped to one colour or intensity. Now we are combining the effect of 3 numbers to arrive at a single colour value. Let’s see an example of that using the blue square at the end of the second row, which has the index [1, 3].

PYTHON

# extract all the colour information for the blue square

upper_right_square = checkerboard[1, 3, :]

upper_right_squareThis outputs: array([ 7, 1, 110]) The integers in order represent Red, Green, and Blue. Looking at the 3 values and knowing how they map, can help us understand why it is blue. If we divide each value by 255, which is the maximum, we can determine how much it is contributing relative to its maximum potential. Effectively, the red is at 7/255 or 2.8 percent of its potential, the green is at 1/255 or 0.4 percent, and blue is 110/255 or 43.1 percent of its potential. So when you mix those three intensities of colour, blue is winning by a wide margin, but the red and green still contribute to make it a slightly different shade of blue than 0,0,110 would be on its own.

These colours mapped to dimensions of the matrix may be referred to as channels. It may be helpful to display each of these channels independently, to help us understand what is happening. We can do that by multiplying our image array representation with a 1d matrix that has a one for the channel we want to keep and zeros for the rest.

If we look at the upper [1, 3] square in all three figures, we can see each of those colour contributions in action. Notice that there are several squares in the blue figure that look even more intensely blue than square [1, 3]. When all three channels are combined though, the blue light of those squares is being diluted by the relative strength of red and green being mixed in with them.

24-bit RGB colour

This last colour model we used, known as the RGB (Red, Green, Blue) model, is the most common.

As we saw, the RGB model is an additive colour model, which means that the primary colours are mixed together to form other colours. Most frequently, the amount of the primary colour added is represented as an integer in the closed range [0, 255] as seen in the example. Therefore, there are 256 discrete amounts of each primary colour that can be added to produce another colour. The number of discrete amounts of each colour, 256, corresponds to the number of bits used to hold the colour channel value, which is eight (28=256). Since we have three channels with 8 bits for each (8+8+8=24), this is called 24-bit colour depth.

Any particular colour in the RGB model can be expressed by a triplet of integers in [0, 255], representing the red, green, and blue channels, respectively. A larger number in a channel means that more of that primary colour is present.

Thinking about RGB colours (5 min)

Suppose that we represent colours as triples (r, g, b), where each of r, g, and b is an integer in [0, 255]. What colours are represented by each of these triples? (Try to answer these questions without reading further.)

- (255, 0, 0)

- (0, 255, 0)

- (0, 0, 255)

- (255, 255, 255)

- (0, 0, 0)

- (128, 128, 128)

- (255, 0, 0) represents red, because the red channel is maximised, while the other two channels have the minimum values.

- (0, 255, 0) represents green.

- (0, 0, 255) represents blue.

- (255, 255, 255) is a little harder. When we mix the maximum value of all three colour channels, we see the colour white.

- (0, 0, 0) represents the absence of all colour, or black.

- (128, 128, 128) represents a medium shade of gray. Note that the 24-bit RGB colour model provides at least 254 shades of gray, rather than only fifty.

Note that the RGB colour model may run contrary to your experience, especially if you have mixed primary colours of paint to create new colours. In the RGB model, the lack of any colour is black, while the maximum amount of each of the primary colours is white. With physical paint, we might start with a white base, and then add differing amounts of other paints to produce a darker shade.

Image formats

Although the images we will manipulate in our programs are conceptualised as rectangular arrays of RGB triplets, they are not necessarily created, stored, or transmitted in that format. There are several image formats we might encounter, and we should know the basics of at least of few of them. Some formats we might encounter, and their file extensions, are shown in this table:

| Format | Extension |

|---|---|

| Device-Independent Bitmap (BMP) | .bmp |

| Joint Photographic Experts Group (JPEG) | .jpg or .jpeg |

| Tagged Image File Format (TIFF) | .tif or .tiff |

BMP

The file format that comes closest to our preceding conceptualisation of images is the Device-Independent Bitmap, or BMP, file format. BMP files store raster graphics images as long sequences of binary-encoded numbers that specify the colour of each pixel in the image. Since computer files are one-dimensional structures, the pixel colours are stored one row at a time. That is, the first row of pixels (those with y-coordinate 0) are stored first, followed by the second row (those with y-coordinate 1), and so on. Depending on how it was created, a BMP image might have 8-bit, 16-bit, or 24-bit colour depth.

24-bit BMP images have a relatively simple file format, can be viewed and loaded across a wide variety of operating systems, and have high quality. However, BMP images are not compressed, resulting in very large file sizes for any useful image resolutions.

The idea of image compression is important to us for two reasons: first, compressed images have smaller file sizes, and are therefore easier to store and transmit; and second, compressed images may not have as much detail as their uncompressed counterparts, and so our programs may not be able to detect some important aspect if we are working with compressed images. Since compression is important to us, we should take a brief detour and discuss the concept.

Image compression

Before discussing additional formats, familiarity with image compression will be helpful. Let’s delve into that subject with a challenge. For this challenge, you will need to know about bits / bytes and how those are used to express computer storage capacities. If you already know, you can skip to the challenge below.

Bits and bytes

Before we talk specifically about images, we first need to understand how numbers are stored in a modern digital computer. When we think of a number, we do so using a decimal, or base-10 place-value number system. For example, a number like 659 is 6 × 102 + 5 × 101 + 9 × 100. Each digit in the number is multiplied by a power of 10, based on where it occurs, and there are 10 digits that can occur in each position (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9).

In principle, computers could be constructed to represent numbers in exactly the same way. But, the electronic circuits inside a computer are much easier to construct if we restrict the numeric base to only two, instead of 10. (It is easier for circuitry to tell the difference between two voltage levels than it is to differentiate among 10 levels.) So, values in a computer are stored using a binary, or base-2 place-value number system.

In this system, each symbol in a number is called a bit instead of a digit, and there are only two values for each bit (0 and 1). We might imagine a four-bit binary number, 1101. Using the same kind of place-value expansion as we did above for 659, we see that 1101 = 1 × 23 + 1 × 22 + 0 × 21 + 1 × 20, which if we do the math is 8 + 4 + 0 + 1, or 13 in decimal.

Internally, computers have a minimum number of bits that they work with at a given time: eight. A group of eight bits is called a byte. The amount of memory (RAM) and drive space our computers have is quantified by terms like Megabytes (MB), Gigabytes (GB), and Terabytes (TB). The following table provides more formal definitions for these terms.

| Unit | Abbreviation | Size |

|---|---|---|

| Kilobyte | KB | 1024 bytes |

| Megabyte | MB | 1024 KB |

| Gigabyte | GB | 1024 MB |

| Terabyte | TB | 1024 GB |

Since image files can be very large, various compression schemes exist for saving (approximately) the same information while using less space. These compression techniques can be categorised as lossless or lossy.

Lossless compression

In lossless image compression, we apply some algorithm (i.e., a computerised procedure) to the image, resulting in a file that is significantly smaller than the uncompressed BMP file equivalent would be. Then, when we wish to load and view or process the image, our program reads the compressed file, and reverses the compression process, resulting in an image that is identical to the original. Nothing is lost in the process – hence the term “lossless.”

The general idea of lossless compression is to somehow detect long patterns of bytes in a file that are repeated over and over, and then assign a smaller bit pattern to represent the longer sample. Then, the compressed file is made up of the smaller patterns, rather than the larger ones, thus reducing the number of bytes required to save the file. The compressed file also contains a table of the substituted patterns and the originals, so when the file is decompressed it can be made identical to the original before compression.

To provide you with a concrete example, consider the 71.5 MB white BMP image discussed above. When put through the zip compression utility on Microsoft Windows, the resulting .zip file is only 72 KB in size! That is, the .zip version of the image is three orders of magnitude smaller than the original, and it can be decompressed into a file that is byte-for-byte the same as the original. Since the original is so repetitious - simply the same colour triplet repeated 25,000,000 times - the compression algorithm can dramatically reduce the size of the file.

If you work with .zip or .gz archives, you are dealing with lossless compression.

Lossy compression

Lossy compression takes the original image and discards some of the detail in it, resulting in a smaller file format. The goal is to only throw away detail that someone viewing the image would not notice. Many lossy compression schemes have adjustable levels of compression, so that the image creator can choose the amount of detail that is lost. The more detail that is sacrificed, the smaller the image files will be - but of course, the detail and richness of the image will be lower as well.

This is probably fine for images that are shown on Web pages or printed off on 4 × 6 photo paper, but may or may not be fine for scientific work. You will have to decide whether the loss of image quality and detail are important to your work, versus the space savings afforded by a lossy compression format.

It is important to understand that once an image is saved in a lossy compression format, the lost detail is just that - lost. I.e., unlike lossless formats, given an image saved in a lossy format, there is no way to reconstruct the original image in a byte-by-byte manner.

JPEG

JPEG images are perhaps the most commonly encountered digital images today. JPEG uses lossy compression, and the degree of compression can be tuned to your liking. It supports 24-bit colour depth, and since the format is so widely used, JPEG images can be viewed and manipulated easily on all computing platforms.

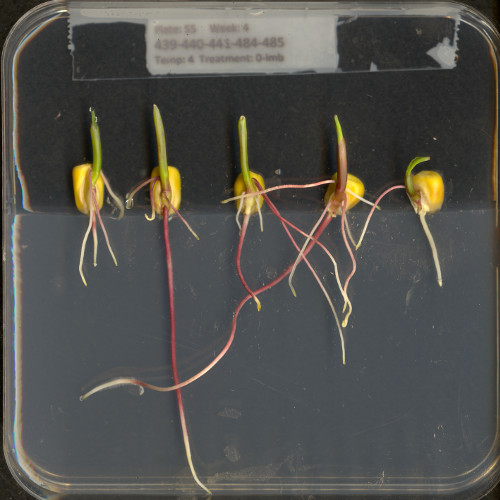

Here is an example showing how JPEG compression might impact image quality. Consider this image of several maize seedlings (scaled down here from 11,339 × 11,336 pixels in order to fit the display).

Now, let us zoom in and look at a small section of the label in the original, first in the uncompressed format:

Here is the same area of the image, but in JPEG format. We used a fairly aggressive compression parameter to make the JPEG, in order to illustrate the problems you might encounter with the format.

The JPEG image is of clearly inferior quality. It has less colour variation and noticeable pixelation. Quality differences become even more marked when one examines the colour histograms for each image. A histogram shows how often each colour value appears in an image. The histograms for the uncompressed (left) and compressed (right) images are shown below:

We learn how to make histograms such as these later on in the workshop. The differences in the colour histograms are even more apparent than in the images themselves; clearly the colours in the JPEG image are different from the uncompressed version.

If the quality settings for your JPEG images are high (and the compression rate therefore relatively low), the images may be of sufficient quality for your work. It all depends on how much quality you need, and what restrictions you have on image storage space. Another consideration may be where the images are stored. For example, if your images are stored in the cloud and therefore must be downloaded to your system before you use them, you may wish to use a compressed image format to speed up file transfer time.

PNG

PNG images are well suited for storing diagrams. It uses a lossless compression and is hence often used in web applications for non-photographic images. The format is able to store RGB and plain luminance (single channel, without an associated color) data, among others. Image data is stored row-wise and then, per row, a simple filter, like taking the difference of adjacent pixels, can be applied to increase the compressability of the data. The filtered data is then compressed in the next step and written out to the disk.

TIFF

TIFF images are popular with publishers, graphics designers, and photographers. TIFF images can be uncompressed, or compressed using either lossless or lossy compression schemes, depending on the settings used, and so TIFF images seem to have the benefits of both the BMP and JPEG formats. The main disadvantage of TIFF images (other than the size of images in the uncompressed version of the format) is that they are not universally readable by image viewing and manipulation software.

Metadata

JPEG and TIFF images support the inclusion of metadata in

images. Metadata is textual information that is contained within an

image file. Metadata holds information about the image itself, such as

when the image was captured, where it was captured, what type of camera

was used and with what settings, etc. We normally don’t see this

metadata when we view an image, but we can view it independently if we

wish to (see Accessing

Metadata, below). The important thing to be aware of at this

stage is that you cannot rely on the metadata of an image being fully

preserved when you use software to process that image. The image

reader/writer library that we use throughout this lesson,

imageio.v3, includes metadata when saving new images but

may fail to keep certain metadata fields. In any case, remember:

if metadata is important to you, take precautions to always

preserve the original files.

Accessing Metadata

imageio.v3 provides a way to display or explore the

metadata associated with an image. Metadata is served independently from

pixel data:

PYTHON

# read metadata

metadata = iio.immeta(uri="data/eight.tif")

# display the format-specific metadata

metadataOUTPUT

{'is_fluoview': False,

'is_nih': False,

'is_micromanager': False,

'is_ome': False,

'is_lsm': False,

'is_reduced': False,

'is_shaped': True,

'is_stk': False,

'is_tiled': False,

'is_mdgel': False,

'compression': <COMPRESSION.NONE: 1>,

'predictor': 1,

'is_mediacy': False,

'description': '{"shape": [5, 3]}',

'description1': '',

'is_imagej': False,

'software': 'tifffile.py',

'resolution_unit': 1,

'resolution': (1.0, 1.0, 'NONE')}Many popular image editing programs have built-in metadata viewing capabilities. A platform-independent open-source tool that allows users to read, write, and edit metadata is ExifTool. It can handle a wide range of file types and metadata formats but requires some technical knowledge to be used effectively. Other software exists that can help you handle metadata, e.g., Fiji and ImageMagick. You may want to explore these options if you need to work with the metadata of your images.

Summary of image formats used in this lesson

The following table summarises the characteristics of the BMP, JPEG, and TIFF image formats:

| Format | Compression | Metadata | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMP | None | None | Universally viewable, high quality | Large file sizes |

| JPEG | Lossy | Yes | Universally viewable, smaller file size | Detail may be lost |

| PNG | Lossless | Yes | Universally viewable, open standard, smaller file size | Metadata less flexible than TIFF, RGB only |

| TIFF | None, lossy, or lossless | Yes | High quality or smaller file size | Not universally viewable |

- Digital images are represented as rectangular arrays of square pixels.

- Digital images use a left-hand coordinate system, with the origin in the upper left corner, the x-axis running to the right, and the y-axis running down. Some learners may prefer to think in terms of counting down rows for the y-axis and across columns for the x-axis. Thus, we will make an effort to allow for both approaches in our lesson presentation.

- Most frequently, digital images use an additive RGB model, with eight bits for the red, green, and blue channels.

- scikit-image images are stored as multi-dimensional NumPy arrays.

- In scikit-image images, the red channel is specified first, then the green, then the blue, i.e., RGB.

- Lossless compression retains all the details in an image, but lossy compression results in loss of some of the original image detail.

- BMP images are uncompressed, meaning they have high quality but also that their file sizes are large.

- JPEG images use lossy compression, meaning that their file sizes are smaller, but image quality may suffer.

- TIFF images can be uncompressed or compressed with lossy or lossless compression.

- Depending on the camera or sensor, various useful pieces of information may be stored in an image file, in the image metadata.

Content from Working with scikit-image

Last updated on 2025-03-31 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How can the scikit-image Python computer vision library be used to work with images?

Objectives

- Read and save images with imageio.

- Display images with Matplotlib.

- Understand RGB vs Multichannel bioimages

- Extract sub-images using array slicing.

We have covered much of how images are represented in computer software. In this episode we will learn some more methods for accessing and changing digital images.

First, import the packages needed for this episode

Reading and displaying images

Imageio provides intuitive functions for reading and writing (saving) images. All of the popular image formats, such as BMP, PNG, JPEG, and TIFF are supported, along with several more esoteric formats. Check the Supported Formats docs for a list of all formats. Matplotlib provides a large collection of plotting utilities.

Let us examine a simple Python program to load, display, and save an image to a different format.

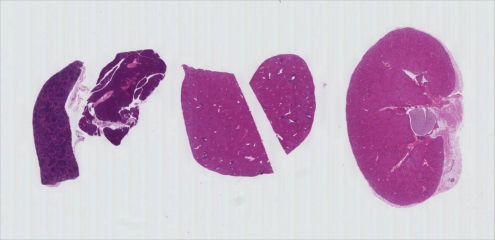

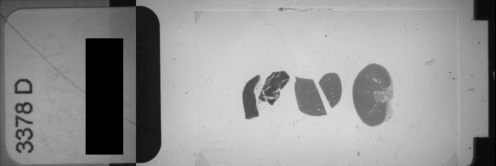

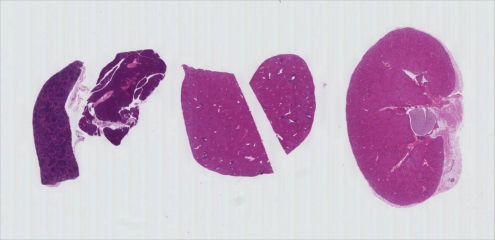

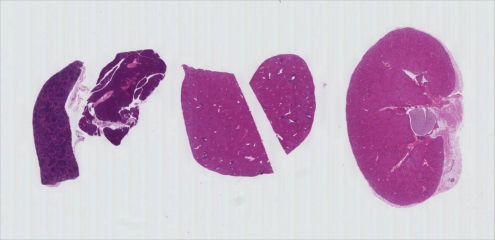

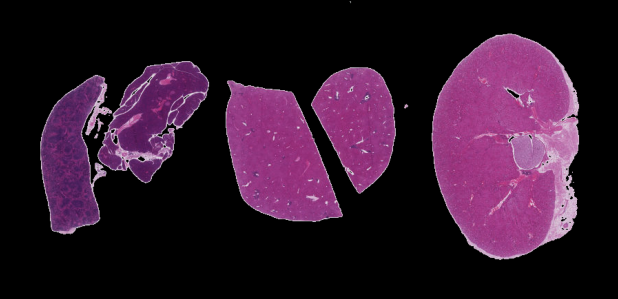

The image we will be using for much of this course is hosted on the JAX public image data repository and was used in a published manuscript from 2023. For simplicity, a lower resolution (smaller) version of the image has been converted to the more universal TIFF format for this workshop.

Here are the first few lines:

PYTHON

"""Python program to open, display, and save an image."""

# read image

he_image = iio.imread(uri="data/he_scale3.tif")We use the iio.imread() function to read a TIFF image

entitled he_scale3. Imageio reads the image, converts

it from TIFF into a NumPy array, and returns the array; we save the

array in a variable named he_image.

Next, we will do something with the image:

Once we have the image in the program, we first call

fig, ax = plt.subplots() so that we will have a fresh

figure with a set of axes independent from our previous calls. Next we

call ax.imshow() in order to display the image.

Saving images

This line,

iio.imwrite(uri="data/he_converted.jpg",image=he_image),

writes the image to a file named he_converted.jpg in the

data/ directory. The imwrite() function

automatically determines the type of the file, based on the file

extension we provide. In this case, the .tif extension

causes the image to be saved as a TIFF, and the .jpg

extension causes the image to be saved as a JPG. Using Finder or File

Explorer, check out the size difference between these two files. As we

discussed in the Image Basics

episode, JPG is performing a lossy compression to save a smaller

file.

Metadata, revisited

Remember, as mentioned in the previous section, images saved with

imwrite() will not retain all metadata associated with the

original image that was loaded into Python! If the image metadata

is important to you, be sure to always keep an unchanged copy of

the original image!

Extensions do not always dictate file type

The iio.imwrite() function automatically uses the file

type we specify in the file name parameter’s extension. Note that this

is not always the case. For example, if we are editing a document in

Microsoft Word, and we save the document as paper.pdf

instead of paper.docx, the file is not saved as a

PDF document.

Named versus positional arguments

When we call functions in Python, there are two ways we can specify the necessary arguments. We can specify the arguments positionally, i.e., in the order the parameters appear in the function definition, or we can use named arguments.

For example, the iio.imwrite() function

definition specifies two parameters, the resource to save the image

to (e.g., a file name, an http address) and the image to write to disk.

So, we could save the chair image in the sample code above using

positional arguments like this:

iio.imwrite("data/he_converted.jpg", he_image)

Since the function expects the first argument to be the file name,

there is no confusion about what "data/he_converted.jpg"

means. The same goes for the second argument.

The style we will use in this workshop is to name each argument, like this:

iio.imwrite(uri="data/he_converted.jpg", image=he_image)

This style will make it easier for you to learn how to use the variety of functions we will cover in this workshop.

Converting colour images to grayscale

It is often easier to work with grayscale images, which have a single

channel, instead of colour images, which have three channels.

scikit-image offers the function ski.color.rgb2gray() to

achieve this. This function adds up the three colour channels in a way

that matches human colour perception, see the

scikit-image documentation for details. It returns a grayscale image

with floating point values in the range from 0 to 1. We can use the

function ski.util.img_as_ubyte() in order to convert it

back to the original data type and the data range back 0 to 255. Note

that it is often better to use image values represented by floating

point values, because using floating point numbers is numerically more

stable.

Colour and color

The Carpentries generally prefers UK English spelling, which is why

we use “colour” in the explanatory text of this lesson. However,

scikit-image contains many modules and functions that include the US

English spelling, color. The exact spelling matters here,

e.g. you will encounter an error if you try to run

ski.colour.rgb2gray(). To account for this, we will use the

US English spelling, color, in example Python code

throughout the lesson. You will encounter a similar approach with

“centre” and center.

PYTHON

"""Python script to load a color image as grayscale."""

# convert to grayscale and display

he_gray = ski.color.rgb2gray(he_image)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.imshow(he_gray, cmap="gray")

It may not be immediately obvious why we would want to do this, but we will see later in the workshop that converting the image to a single value is very helpful for downstream processing such as segmentation.

Loading images with imageio: Pixel type and depth

When loading certain image types in Python, the pixel values are

stored as 8-bit integer numbers that can take values in the range 0-255.

However, pixel values may also be stored with other types and ranges.

For example, some scikit-image functions return the pixel values as

floating point numbers in the range 0-1. The type and range of the pixel

values are important for the colorscale when plotting, and for masking

and thresholding images as we will see later in the lesson. If you are

unsure about the type of the pixel values, you can inspect it with

print(image.dtype). For the example above, you should find

that it is dtype('uint8') indicating 8-bit integer

numbers.

Multichannel images

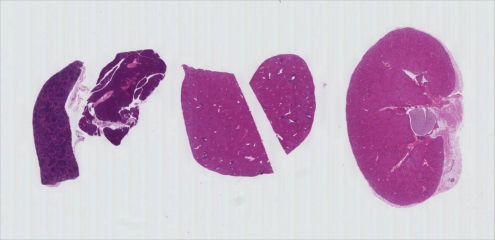

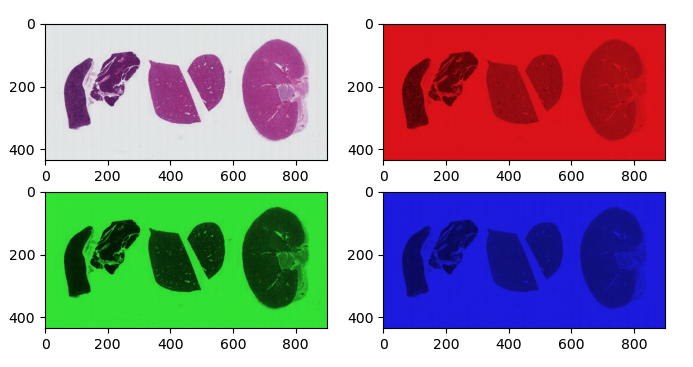

In the Image Basics episode we discussed how color is represented by three numbers in RGB images. The H&E image we have been using is an RGB image. The tissue was stained with hematoxylin (blue) and eosin (pink), but if we split apart the RGB color channels, each one isn’t particularly useful in identifying that staining:

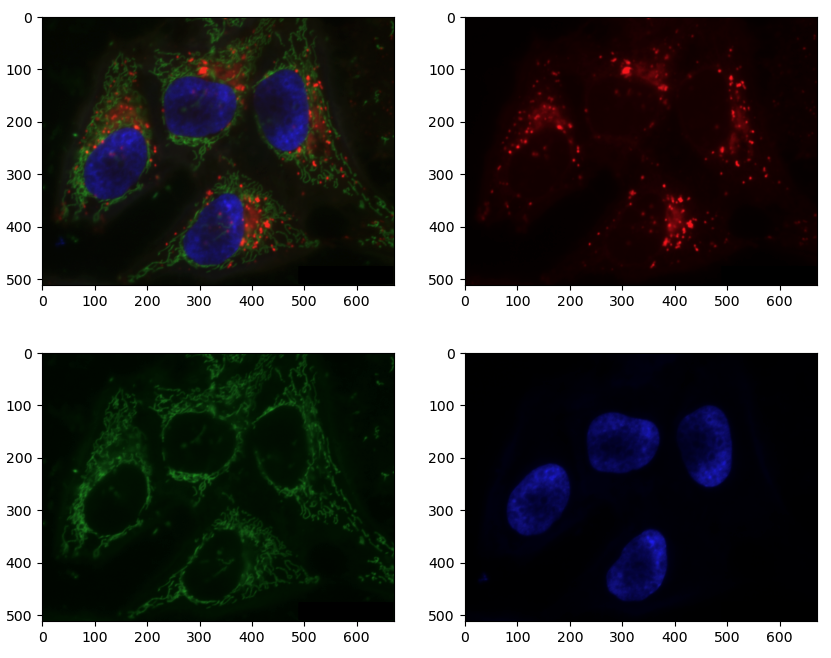

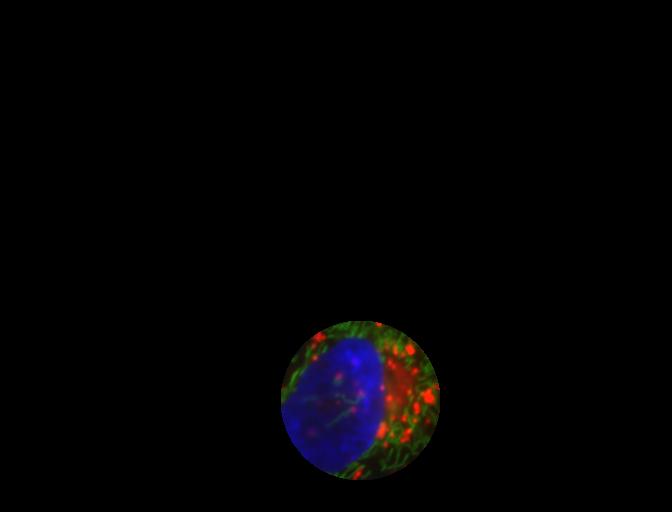

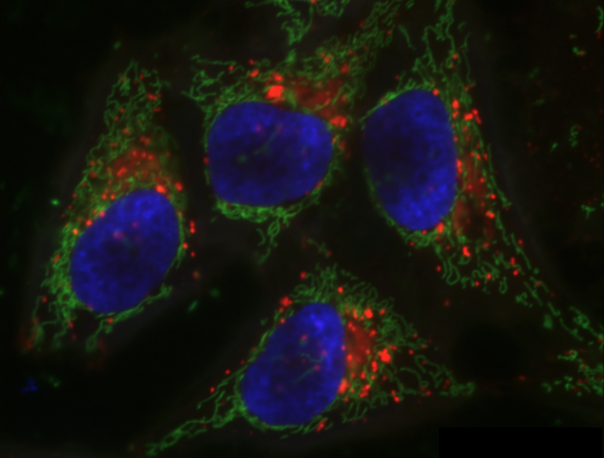

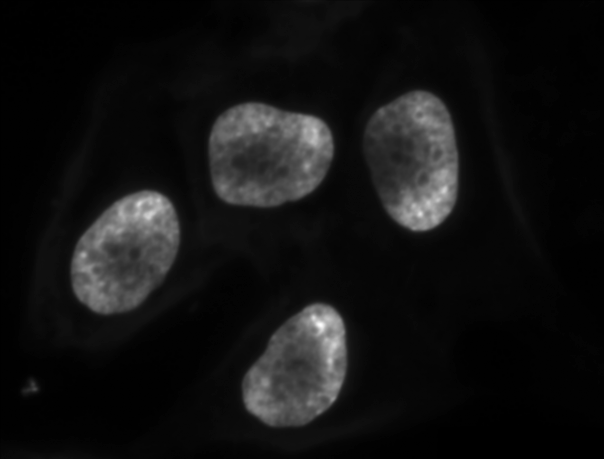

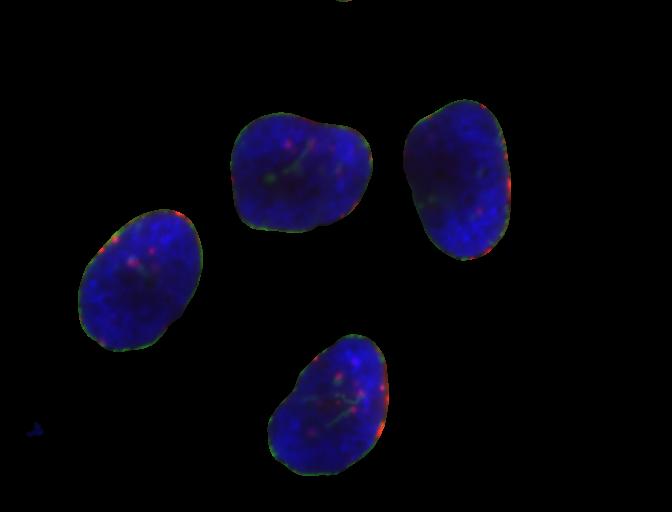

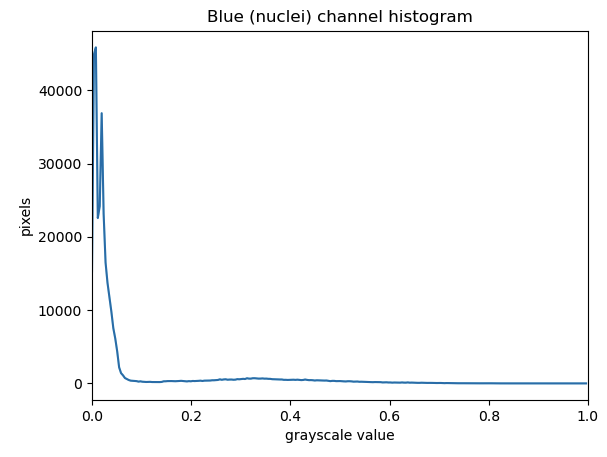

In contrast, the image of HeLa cells is a multichannel image. We can conveniently read it and view it using the same functions as RGB, since it’s still 8bit with three channels. But in reality, those channels represent fluorescence of three different parts of the cell: lysosomes, mitochondria and nucleus. Currently, the lysosomes are marked in red, mitochondria in green, and nucleus in blue, but it doesn’t really matter what color each is represented by. It’s often more useful to view multichannel images one channel at a time.

PYTHON

cells = iio.imread(uri="data/hela-cells-8bit.tif")

nuclei = cells[:,:,2]

mitochondria = cells[:,:,1]

fig, ax = plt.subplots(ncols=2)

ax[0].imshow(nuclei)

ax[1].imshow(mitochondria, vmax=255)Plotting single channel images (cmap, vmin, vmax)

Compared to a colour image, a grayscale image or a single channel

contains only a single intensity value per pixel. When we plot such an

image with ax.imshow, Matplotlib uses a colour map, to

assign each intensity value a colour. The default colour map is called

“viridis” and maps low values to purple and high values to yellow. We

can instruct Matplotlib to map low values to black and high values to

white instead, by calling ax.imshow with

cmap="gray". The

documentation contains an overview of pre-defined colour maps.

Furthermore, Matplotlib determines the minimum and maximum values of

the colour map dynamically from the image, by default. That means that

in an image where the minimum is 64 and the maximum is 192, those values

will be mapped to black and white respectively (and not dark gray and

light gray as you might expect). If there are defined minimum and

maximum vales, you can specify them via vmin and

vmax to get the desired output.

If you forget about this, it can lead to unexpected results.

Access via slicing

As noted in the previous lesson scikit-image images are stored as NumPy arrays, so we can use array slicing to select rectangular areas of an image. Then, we can save the selection as a new image, change the pixels in the image, and so on. It is important to remember that coordinates are specified in (ry, cx) order and that colour values are specified in (r, g, b) order when doing these manipulations.

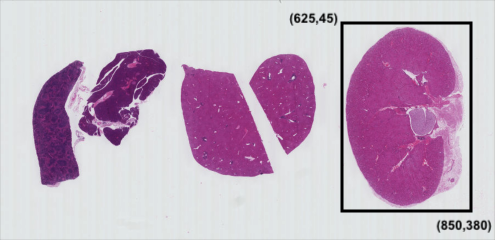

Consider our H&E image, and suppose we want to create a sub-image of just one of the tissue sections.

Using matplotlib.pyplot.imshow we can determine the

coordinates of the corners of the area we wish to extract by hovering

the mouse near the points of interest and noting the coordinates

(remember to run %matplotlib widget first if you haven’t

already). If we do that, we might settle on a rectangular area with an

upper-left coordinate of (625, 45) and a lower-right coordinate

of (850, 380), as shown in this version of the HeLa

picture:

Note that the coordinates in the preceding image are specified in

(cx, ry) order. Now if our entire HeLa cell image is stored as

a NumPy array named image, we can create a new image of the

selected region with a statement like this:

clip = image[45:381, 625:851, :]

Our array slicing specifies the range of y-coordinates or rows first,

45:381, and then the range of x-coordinates or columns,

625:851. Note we go one beyond the maximum value in each

dimension, so that the entire desired area is selected, because the

sliced area does not include the upper bound index. The third part of

the slice, :, indicates that we want all three colour

channels in our new image.

A script to create the subimage would start by loading the image:

PYTHON

"""Python script demonstrating image modification and creation via NumPy array slicing."""

# load and display original image

he_image = iio.imread(uri="data/he_scale3.tif")

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.imshow(he_image)Then we use array slicing to create a new image with our selected area and then display the new image.

PYTHON

# extract, display, and save sub-image

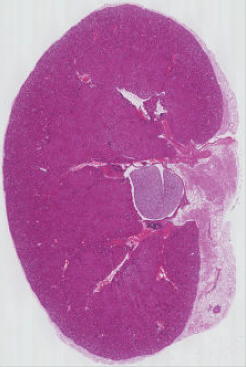

kidney = he_image[45:381, 625:851, :]

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.imshow(kidney)

iio.imwrite(uri="data/kidney.tif", image=kidney)

Challenge

Practicing with slices (10 min) Repeat the above exercise for the leftmost tissue section in the H&E image.

Solution Here is the completed Python program to select only the leftmost cell in the image

“““Python script to extract a sub-image containing only the leftmost cell in an existing image.”“”

PYTHON

# load and display original image

he_image = iio.imread(uri="data/he_scale3.tif")

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.imshow(he_image)

# extract and display sub-image

tissue = he_image[80:351, 50:311, :]

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.imshow(tissue)

# save sub-image

iio.imwrite(uri="data/tissue.jpg", image=tissue)- Images are read from disk with the

iio.imread()function. - We create a window that automatically scales the displayed image

with Matplotlib and calling

imshow()on the global figure object. - Colour images can be transformed to grayscale using

ski.color.rgb2gray()or, in many cases, be read as grayscale directly by passing the argumentmode="L"toiio.imread(). - Array slicing can be used to extract sub-images or modify areas of

images, e.g.,

clip = image[45:381, 625:851, :]. - Metadata is not retained when images are loaded as NumPy arrays

using

iio.imread().

Content from Drawing and Bitwise Operations

Last updated on 2025-03-31 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How can we draw on scikit-image images and use bitwise operations and masks to select certain parts of an image?

Objectives

- Create a blank, black scikit-image image.

- Draw rectangles and other shapes on scikit-image images.

- Explain how a white shape on a black background can be used as a mask to select specific parts of an image.

- Use bitwise operations to apply a mask to an image.

The next series of episodes covers a basic toolkit of scikit-image operators. With these tools, we will be able to create programs to perform simple analyses of images based on changes in colour or shape.

First, import the packages needed for this episode

PYTHON

import imageio.v3 as iio

import ipympl

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import skimage as ski

%matplotlib widgetHere, we import the same packages as earlier in the lesson.

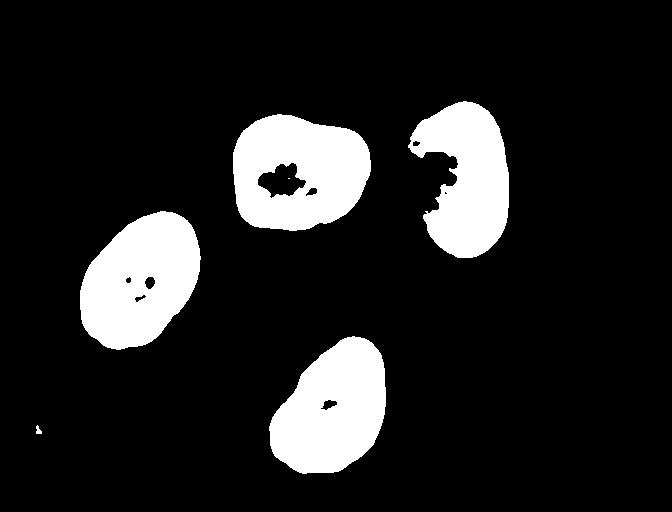

Drawing on images

Often we wish to select only a portion of an image to analyze, and ignore the rest. Creating a rectangular sub-image with slicing, as we did in the Working with scikit-image episode is one option for simple cases. Another option is to create another special image, of the same size as the original, with white pixels indicating the region to save and black pixels everywhere else. Such an image is called a mask. In preparing a mask, we sometimes need to be able to draw a shape - a circle or a rectangle, say - on a black image. scikit-image provides tools to do that.

As an example, we will edit the pixels of the slide label from our H&E macro image. This could be helpful if there were information there we wanted to obfuscate.

A Python program to create a mask to select only that area of the image would start with a now-familiar section of code to open and display the original image:

PYTHON

# Load and display the original image

macro_image = iio.imread(uri="data/he_macro.tif")

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.imshow(macro_image)

We load and display the initial image in the same way we have done before.

NumPy allows indexing of images/arrays with “boolean” arrays of the

same size. Indexing with a boolean array is also called mask indexing.

The “pixels” in such a mask array can only take two values:

True or False. When indexing an image with

such a mask, only pixel values at positions where the mask is

True are accessed. But first, we need to generate a mask

array of the same size as the image. Luckily, the NumPy library provides

a function to create just such an array. The next section of code shows

how:

The first argument to the ones() function is the shape

of the original image, so that our mask will be exactly the same size as

the original. Notice, that we have only used the first two indices of

our shape. We omitted the channel dimension. Indexing with such a mask

will change all channel values simultaneously. The second argument,

dtype = "bool", indicates that the elements in the array

should be booleans - i.e., values are either True or

False. Thus, even though we use np.ones() to

create the mask, its pixel values are in fact not 1 but

True. You could check this, e.g., by

print(mask[0, 0]).

Next, we draw a filled, rectangle on the mask:

PYTHON

# Draw filled rectangle on the mask image

rr, cc = ski.draw.rectangle(start=(100, 210), end=(381,301))

mask[rr, cc] = True

# Display mask image

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

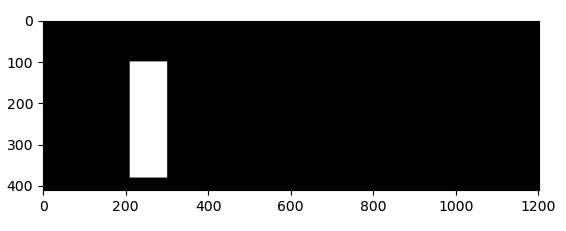

ax.imshow(mask, cmap="gray")Here is what our constructed mask looks like:

The parameters of the rectangle() function

(100, 210) and (381,301), are the coordinates

of the upper-left (start) and lower-right

(end) corners of a rectangle in (ry, cx) order.

The function returns the rectangle as row (rr) and column

(cc) coordinate arrays.

Check the documentation!

When using an scikit-image function for the first time - or the fifth

time - it is wise to check how the function is used, via the scikit-image

documentation or other usage examples on programming-related sites

such as Stack Overflow. Basic

information about scikit-image functions can be found interactively in

Python, via commands like help(ski) or

help(ski.draw.rectangle). Take notes in your lab notebook.

And, it is always wise to run some test code to verify that the

functions your program uses are behaving in the manner you intend.

Variable naming conventions!

You may have wondered why we called the return values of the

rectangle function rr and cc?! You may have

guessed that r is short for row and

c is short for column. However, the rectangle

function returns mutiple rows and columns; thus we used a convention of

doubling the letter r to rr (and

c to cc) to indicate that those are multiple

values. In fact it may have even been clearer to name those variables

rows and columns; however this would have been

also much longer. Whatever you decide to do, try to stick to some

already existing conventions, such that it is easier for other people to

understand your code.

Other drawing operations (15 min)

There are other functions for drawing on images, in addition to the

ski.draw.rectangle() function. We can draw circles, lines,

text, and other shapes as well. These drawing functions may be useful

later on, to help annotate images that our programs produce. Practice

some of these functions here.

Circles can be drawn with the ski.draw.disk() function,

which takes two parameters: the (ry, cx) point of the centre of the

circle, and the radius of the circle. There is an optional

shape parameter that can be supplied to this function. It

will limit the output coordinates for cases where the circle dimensions

exceed the ones of the image.

Lines can be drawn with the ski.draw.line() function,

which takes four parameters: the (ry, cx) coordinate of one end of the

line, and the (ry, cx) coordinate of the other end of the line.

Other drawing functions supported by scikit-image can be found in the scikit-image reference pages.

First let’s make an empty, black image with a size of 800x600 pixels.

Recall that a colour image has three channels for the colours red,

green, and blue (RGB, cf. Image

Basics). Hence we need to create a 3D array of shape

(600, 800, 3) where the last dimension represents the RGB

colour channels.

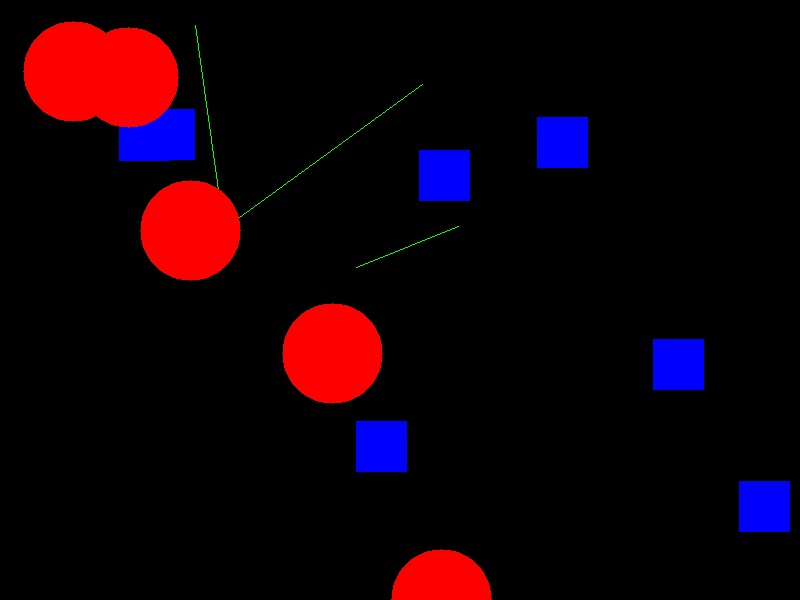

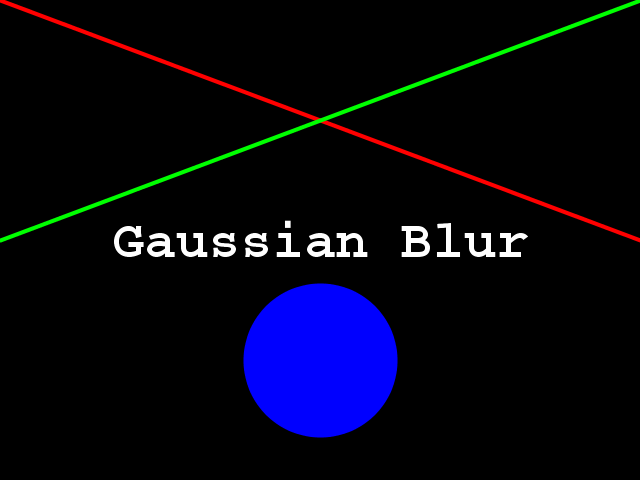

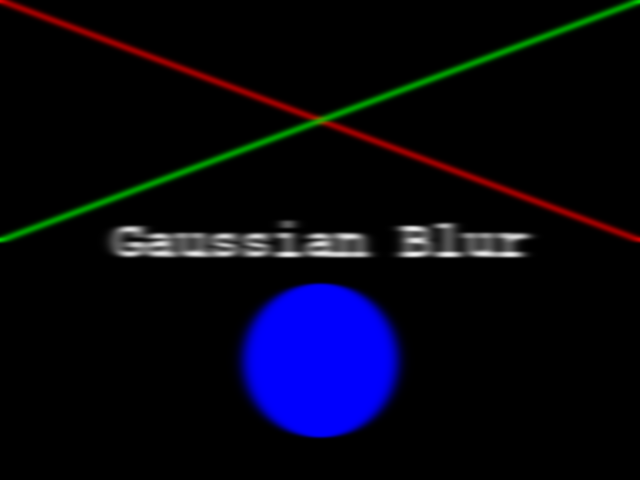

Now your task is to draw some other coloured shapes and lines on the image, perhaps something like this:

Drawing a circle:

PYTHON

# Draw a blue circle with centre (200, 300) in (ry, cx) coordinates, and radius 100

rr, cc = ski.draw.disk(center=(200, 300), radius=100, shape=canvas.shape[0:2])

canvas[rr, cc] = (0, 0, 255)Drawing a line:

PYTHON

# Draw a green line from (400, 200) to (500, 700) in (ry, cx) coordinates

rr, cc = ski.draw.line(r0=400, c0=200, r1=500, c1=700)

canvas[rr, cc] = (0, 255, 0)We could expand this solution, if we wanted, to draw rectangles,

circles and lines at random positions within our black canvas. To do

this, we could use the random python module, and the

function random.randrange, which can produce random numbers

within a certain range.

Let’s draw 15 randomly placed circles:

PYTHON

import random

# create the black canvas

canvas = np.zeros(shape=(600, 800, 3), dtype="uint8")

# draw a blue circle at a random location 15 times

for i in range(15):

rr, cc = ski.draw.disk(center=(

random.randrange(600),

random.randrange(800)),

radius=50,

shape=canvas.shape[0:2],

)

canvas[rr, cc] = (0, 0, 255)

# display the results

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.imshow(canvas)We could expand this even further to also randomly choose whether to

plot a rectangle, a circle, or a square. Again, we do this with the

random module, now using the function

random.random that returns a random number between 0.0 and

1.0.

PYTHON

import random

# Draw 15 random shapes (rectangle, circle or line) at random positions

for i in range(15):

# generate a random number between 0.0 and 1.0 and use this to decide if we

# want a circle, a line or a sphere

x = random.random()

if x < 0.33:

# draw a blue circle at a random location

rr, cc = ski.draw.disk(center=(

random.randrange(600),

random.randrange(800)),

radius=50,

shape=canvas.shape[0:2],

)

color = (0, 0, 255)

elif x < 0.66:

# draw a green line at a random location

rr, cc = ski.draw.line(

r0=random.randrange(600),

c0=random.randrange(800),

r1=random.randrange(600),

c1=random.randrange(800),

)

color = (0, 255, 0)

else:

# draw a red rectangle at a random location

rr, cc = ski.draw.rectangle(

start=(random.randrange(600), random.randrange(800)),

extent=(50, 50),

shape=canvas.shape[0:2],

)

color = (255, 0, 0)

canvas[rr, cc] = color

# display the results

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.imshow(canvas)Image modification

All that remains is the task of modifying the image using our mask in

such a way that the areas with True pixels in the mask are

not shown in the image any more.

Loading images with imageio: Read-only arrays

When loading an image with imageio, in certain situations the image

is stored in a read-only array. If you attempt to manipulate the pixels

in a read-only array, you will receive an error message

ValueError: assignment destination is read-only. In order

to make the image array writeable, we can create a copy with

image = np.array(image) before manipulating the pixel

values.

How does a mask work? (optional, not included in timing)

Now, consider the mask image we created above. The values of the mask

that corresponds to the portion of the image we are interested in are

all False, while the values of the mask that corresponds to

the portion of the image we want to remove are all

True.

How do we change the original image using the mask?

When indexing the image using the mask, we access only those pixels

at positions where the mask is True. So, when indexing with

the mask, one can set those values to 0, and effectively remove them

from the image.

Now we can write a Python program to use a mask to retain only the leftmost cell of the HeLa cells image. We load the original image and create the mask in the same way as before:

PYTHON

# Load the original image

macro_image = iio.imread(uri="data/he_macro.tif")

macro_image = np.array(macro_image)

# Create the basic mask

mask = np.ones(shape=cells.shape[0:2], dtype="bool")

# Draw a filled rectangle on the mask image

rr, cc = ski.draw.rectangle(start=(100, 210), end=(381,301))

mask[rr, cc] = TrueThen, we use NumPy indexing to remove the portions of the image,

where the mask is True:

Then, we display the masked image.

The resulting masked image should look like this:

- We can use the NumPy

zeros()function to create a blank, black image. - We can draw on scikit-image images with functions such as

ski.draw.rectangle(),ski.draw.disk(),ski.draw.line(), and more. - The drawing functions return indices to pixels that can be set directly.

Content from Creating Histograms

Last updated on 2025-03-31 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How can we create grayscale and colour histograms to understand the distribution of colour values in an image?

Objectives

- Explain what a histogram is.

- Load an image in grayscale format.

- Create and display grayscale and colour histograms for entire images.

- Create and display grayscale and colour histograms for certain areas of images, via masks.

In this episode, we will learn how to use scikit-image functions to create and display histograms for images.

First, import the packages needed for this episode

Introduction to Histograms

As it pertains to images, a histogram is a graphical representation showing how frequently various colour values occur in the image. We saw in the Image Basics episode that we could use a histogram to visualise the differences in uncompressed and compressed image formats. If your project involves detecting colour changes between images, histograms will prove to be very useful, and histograms are also quite handy as a preparatory step before performing thresholding.

Grayscale Histograms

We will start with grayscale images, and then move on to colour images. We will use this H&E image as an example:

Here we load the image in grayscale instead of full colour, and display it:

PYTHON

# read the H&E image as grayscale from the outset

he_image = iio.imread(uri="data/he_scale3.tif")

he_image = ski.color.rgb2gray(he_image)

# convert the image to float dtype with a value range from 0 to 1

he_image = ski.util.img_as_float(he_image)

# display the image

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.imshow(he_image, cmap="gray")

Again, we use the iio.imread() function to load our

image. Then, we convert the grayscale image of integer dtype, with 0-255

range, into a floating-point one with 0-1 range, by calling the function

ski.util.img_as_float. We can also calculate histograms for

8 bit images as we will see in the subsequent exercises.

We now use the function np.histogram to compute the

histogram of our image which, after all, is a NumPy array:

The parameter bins determines the number of “bins” to

use for the histogram. We pass in 256 because we want to

see the pixel count for each of the 256 possible values in the grayscale

image.

The parameter range is the range of values each of the

pixels in the image can have. Here, we pass 0 and 1, which is the value

range of our input image after conversion to floating-point.

The first output of the np.histogram function is a

one-dimensional NumPy array, with 256 rows and one column, representing

the number of pixels with the intensity value corresponding to the

index. I.e., the first number in the array is the number of pixels found

with intensity value 0, and the final number in the array is the number

of pixels found with intensity value 255. The second output of

np.histogram is an array with the bin edges and one column

and 257 rows (one more than the histogram itself). There are no gaps

between the bins, which means that the end of the first bin, is the

start of the second and so on. For the last bin, the array also has to

contain the stop, so it has one more element, than the histogram.

Next, we turn our attention to displaying the histogram, by taking advantage of the plotting facilities of the Matplotlib library.

PYTHON

# configure and draw the histogram figure

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.set_title("Grayscale Histogram")

ax.set_xlabel("grayscale value")

ax.set_ylabel("pixel count")

ax.set_xlim([0.0, 1.0]) # <- named arguments do not work here

ax.plot(bin_edges[0:-1], histogram) # <- or hereWe create the plot with plt.subplots(), then label the

figure and the coordinate axes with ax.set_title(),

ax.set_xlabel(), and ax.set_ylabel()

functions. The last step in the preparation of the figure is to set the

limits on the values on the x-axis with the

ax.set_xlim([0.0, 1.0]) function call.

Variable-length argument lists

Note that we cannot used named parameters for the

ax.set_xlim() or ax.plot() functions. This is

because these functions are defined to take an arbitrary number of

unnamed arguments. The designers wrote the functions this way

because they are very versatile, and creating named parameters for all

of the possible ways to use them would be complicated.

Finally, we create the histogram plot itself with

ax.plot(bin_edges[0:-1], histogram). We use the

left bin edges as x-positions for the histogram values

by indexing the bin_edges array to ignore the last value

(the right edge of the last bin). When we run the

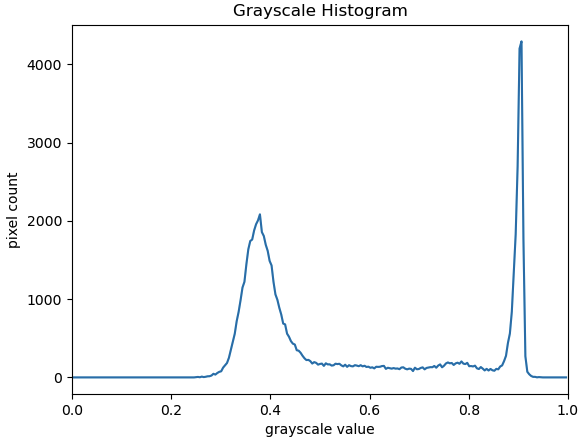

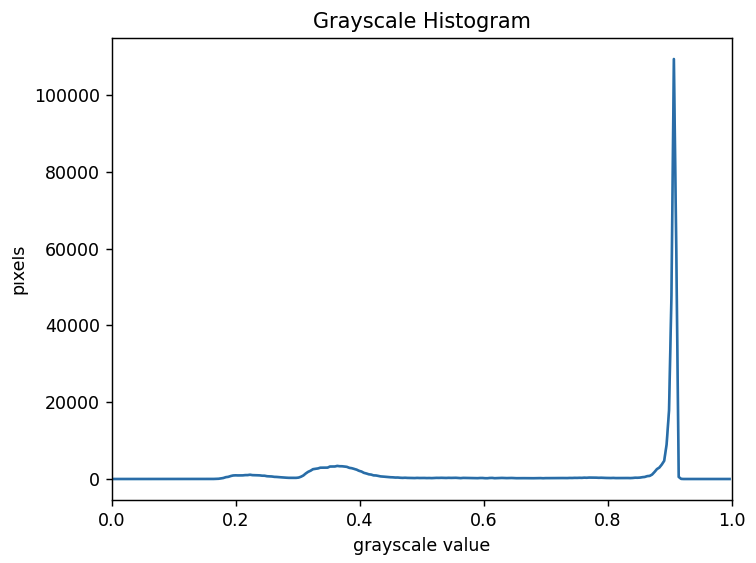

program on the H&E image, it produces this histogram:

Histograms in Matplotlib

Matplotlib provides a dedicated function to compute and display

histograms: ax.hist(). We will not use it in this lesson in

order to understand how to calculate histograms in more detail. In

practice, it is a good idea to use this function, because it visualises

histograms more appropriately than ax.plot(). Here, you

could use it by calling

ax.hist(image.flatten(), bins=256, range=(0, 1)) instead of

np.histogram() and ax.plot()

(*.flatten() is a NumPy function that converts our

two-dimensional image into a one-dimensional array).

Histograms with slicing and masks

There are a lot of white background pixels in the image, so it’s hard to see where the peak for the tissue color is in the histogram. It’s often useful to slice around the regions of interest to get more information from histograms. We will use the slicing from Working with scikit-image to get a histogram of just the kidney section:

PYTHON

# get the subimage of just the kidney section

kidney = he_image[45:381, 625:851]

kidney_histogram, kidney_bin_edges = np.histogram(kidney, bins=256, range=(0, 1))

# configure and draw the histogram figure

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.set_title("Grayscale Histogram")

ax.set_xlabel("grayscale value")

ax.set_ylabel("pixel count")

ax.set_xlim([0.0, 1.0]) # <- named arguments do not work here

ax.plot(bin_edges[0:-1], kidney_histogram) # <- or here

Colour Histograms

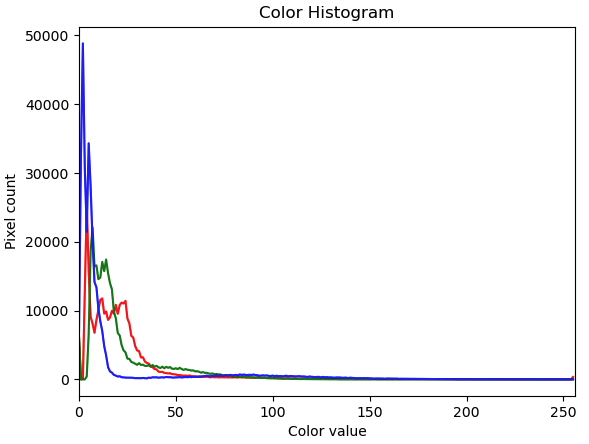

We can also create histograms for full colour images, in addition to grayscale histograms. A program to create colour histograms starts in a familiar way:

PYTHON

# read original image, in full color

cells = iio.imread(uri="data/hela-cells-8bit.tif")

# display the image

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.imshow(cells)We read the original image, now in full colour, and display it.

Next, we create the histogram, by calling the

np.histogram function three times, once for each of the

channels. We obtain the individual channels, by slicing the image along

the last axis. For example, we can obtain the red colour channel by

calling r_chan = image[:, :, 0].

PYTHON

# tuple to select colors of each channel line

colors = ("red", "green", "blue")

# create the histogram plot, with three lines, one for

# each color

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.set_xlim([0, 256])

for channel_id, color in enumerate(colors):

histogram, bin_edges = np.histogram(

cells[:, :, channel_id], bins=256, range=(0, 256)

)

ax.plot(bin_edges[0:-1], histogram, color=color)

ax.set_title("Color Histogram")

ax.set_xlabel("Color value")

ax.set_ylabel("Pixel count")We will draw the histogram line for each channel in a different colour, and so we create a tuple of the colours to use for the three lines with the

colors = ("red", "green", "blue")

line of code. Then, we limit the range of the x-axis with the

ax.set_xlim() function call.

Next, we use the for control structure to iterate

through the three channels, plotting an appropriately-coloured histogram

line for each. This may be new Python syntax for you, so we will take a

moment to discuss what is happening in the for

statement.

The Python built-in enumerate() function takes a list

and returns an iterator of tuples, where the first

element of the tuple is the index and the second element is the element

of the list.

Iterators, tuples, and

enumerate()

In Python, an iterator, or an iterable object, is

something that can be iterated over with the for control

structure. A tuple is a sequence of objects, just like a list.

However, a tuple cannot be changed, and a tuple is indicated by

parentheses instead of square brackets. The enumerate()

function takes an iterable object, and returns an iterator of tuples

consisting of the 0-based index and the corresponding object.

For example, consider this small Python program:

Executing this program would produce the following output:

OUTPUT

(0, 'a')

(1, 'b')

(2, 'c')

(3, 'd')

(4, 'e')In our colour histogram program, we are using a tuple,

(channel_id, color), as the for variable. The

first time through the loop, the channel_id variable takes

the value 0, referring to the position of the red colour

channel, and the color variable contains the string

"red". The second time through the loop the values are the

green channels index 1 and "green", and the

third time they are the blue channel index 2 and

"blue".

Inside the for loop, our code looks much like it did for

the grayscale example. We calculate the histogram for the current

channel with the

histogram, bin_edges = np.histogram(image[:, :, channel_id], bins=256, range=(0, 256))

function call, and then add a histogram line of the correct colour to the plot with the

ax.plot(bin_edges[0:-1], histogram, color=color)

function call. Note the use of our loop variables,

channel_id and color.

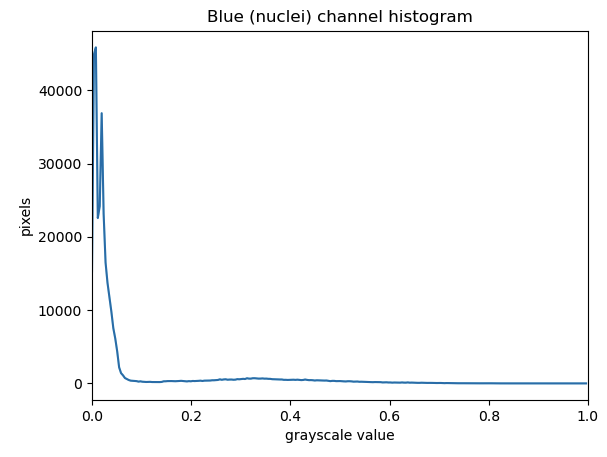

Finally we label our axes and display the histogram, shown here:

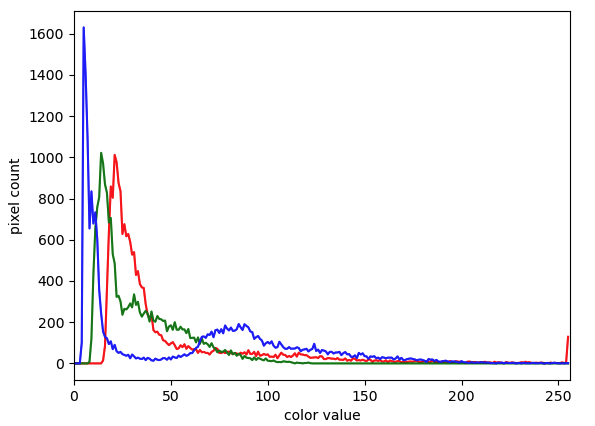

Colour histogram with a mask (25 min)

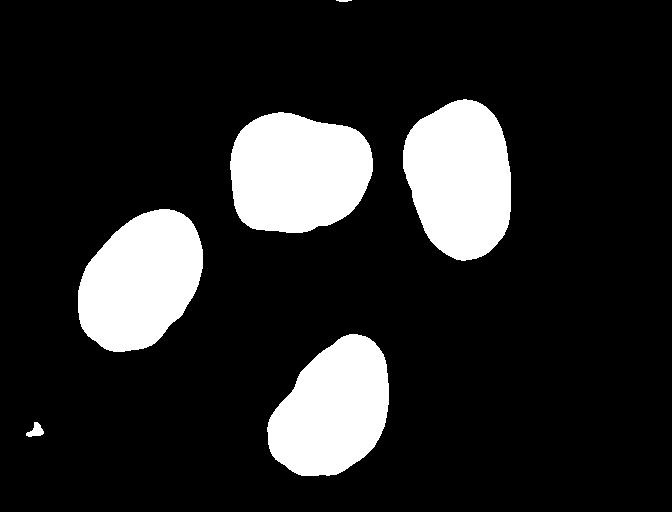

Looking at the histogram above, you will notice that there is a large number of very dark pixels in each channel. This is not so surprising, since the image has a mostly black background. What if we want to focus on a more foreground part of the image, like just one of the cells. This is where a mask enters the picture!

Hover over the image with your mouse to find the centre of that cell and the radius (in pixels) of the cell. Then, using techniques from the Drawing and Bitwise Operations episode, create a circular mask to select only the desired cell. Then, use that mask to apply the colour histogram operation to that cell.

Your masked image should look something like this:

And, the program should produce a colour histogram that looks like this:

PYTHON

# create a circular mask to select the lowest cell in the image

mask = np.zeros(shape=cells.shape[0:2], dtype="bool")

circle = ski.draw.disk(center=(400, 360), radius=80, shape=cells.shape[0:2])

mask[circle] = 1

# just for display:

# make a copy of the image, call it masked_image, and

# zero values where mask is False

masked_img = np.array(cells)

masked_img[~mask] = 0

# create a new figure and display masked_img, to verify the

# validity of your mask

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.imshow(masked_img)

# list to select colors of each channel line

colors = ("red", "green", "blue")

# create the histogram plot, with three lines, one for

# each color

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.set_xlim([0, 256])

for (channel_id, color) in enumerate(colors):

# use your circular mask to apply the histogram

# operation to the lowest cell of the image

histogram, bin_edges = np.histogram(

cells[:, :, channel_id][mask], bins=256, range=(0, 256)

)

ax.plot(histogram, color=color)

ax.set_xlabel("color value")

ax.set_ylabel("pixel count")- We can create histograms of images with the

np.histogramfunction. - We can display histograms using

ax.plot()with thebin_edgesandhistogramvalues returned bynp.histogram(). - The plot can be customised using

ax.set_xlabel(),ax.set_ylabel(),ax.set_xlim(),ax.set_ylim(), andax.set_title(). - We can separate the colour channels of an RGB image using slicing operations and create histograms for each colour channel separately.

Content from Blurring Images

Last updated on 2025-03-18 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How can we apply a low-pass blurring filter to an image?

Objectives

- Explain why applying a low-pass blurring filter to an image is beneficial.

- Apply a Gaussian blur filter to an image using scikit-image.

In this episode, we will learn how to use scikit-image functions to blur images.

When processing an image, we are often interested in identifying objects represented within it so that we can perform some further analysis of these objects, e.g., by counting them, measuring their sizes, etc. An important concept associated with the identification of objects in an image is that of edges: the lines that represent a transition from one group of similar pixels in the image to another different group. One example of an edge is the pixels that represent the boundaries of an object in an image, where the background of the image ends and the object begins.

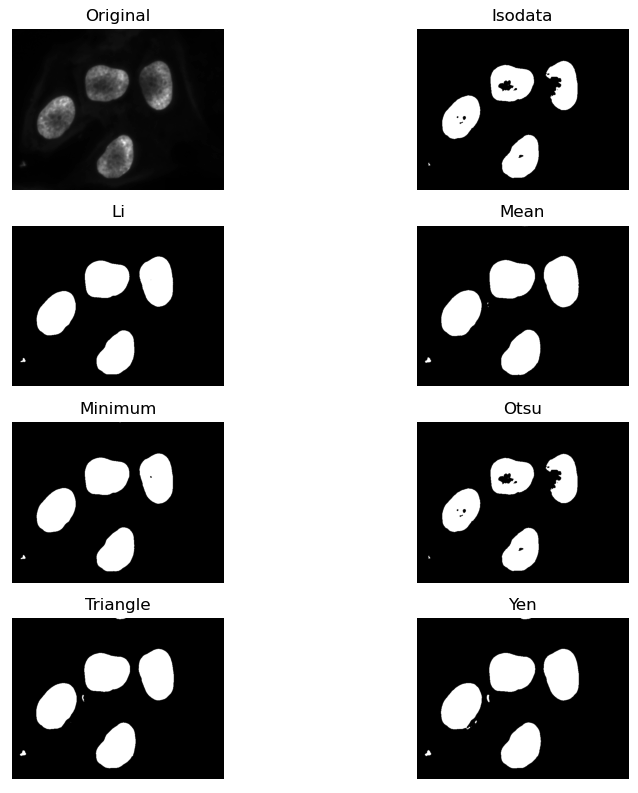

When we blur an image, we make the colour transition from one side of